|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback

ISSUE

29

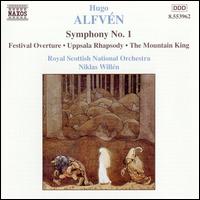

Alfvén Orchestral Works, vol. 1

Festspel, Op. 25. Suite from Bergakungen. Uppsalarapsodi, Op. 24 (Svensk rapsodi nr. 2). Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 7. Royal Scottish National Orchestra/Niklas Willén, Naxos 8.553962. TT: 70:32.

Hugo Alfvén—painter, writer, and composer—apparently represents the musical spirit of Sweden, though little of his music seems regularly to have made its way south of the Kattegat. A few of the symphonies have sporadically turned up here on Caprice and Swedish Society Discofil, on both vinyl and silver discs, but the ready availability of the Naxos series should bring the composer's well-wrought oeuvre to a wider public. Many listeners will make reflexive comparisons with Edvard Grieg, the only Scandinavian composer with whom they might already be familiar. (Sibelius doesn't count—Finland isn't part of Scandinavia, remember.) Although Alfvén was well-versed in Swedish folk tradition, his themes generally lack the strong folklike profile of Grieg's, so their appeal is less immediate and infectious. On the other hand, Alfvén's more fluid melodic gift avoids the short-windedness that can beset Grieg, especially in regular four-bar phrases. On this hearing, I'm not sure that the First Symphony is the best starting point for a newcomer: it's frequently lovely, but uneven in inspiration. After the melancholy slow introduction, the first movement's main themes are agreeable but conventionally "dramatic"; only in the development does the 27-year-old composer begin to explore a wider expressive range (and the clarinet's toy-march effect in the recapitulation is a nice touch). At the start of the Andante, strings and then clarinet strain at post-Wagnerian harmonic gestures, before settling into more comforting, and more comfortable, progressions; the clarinet, again, conjures a desolate moment near the close. The Allegro molto scherzando makes a nice contrast with its grave, weighty choralelike trio. In the finale, Alfvén turns the nice trick of making the rhythmically active opening theme sound serene; but when a completely unrelated group in duple time follows, it becomes difficult to fathom the shape of the movement, which chugs on a bit too long. The movement titles for the Bergakungen (Mountain King) suite may suggest Grieg, but only the concluding Vallflickans dans (Dance of the Shepherd Girl), with its hardanger—style fiddling and its sombre central section, bears out the suggestion. The stark open textures and obsessive rhythms of the opening Besvärjelse (Invocation) recall Mussorgsky; the searching viola and wispy woodwind responses of Trollflickans dans (Dance of the Troll Maiden) set off an oddly American-sounding string melody; and Sommarregn (Summer Rain) is impressionist tone-painting around a lonely, ruminative solo trumpet. Festspel is suitably festive, colorful and appealing, though I somehow didn't expect a Swedish overture to take the form of a Polonaise: it's a Nordic counterpart to the big Eugene Onegin number, flowing second theme and all. The second Swedish Rhapsody is, as its title suggests, a free-form structure, varied in mood, attractive except in a plotzy, flatfooted passage beginning at [~7:15]. Under Niklas Willén's sympathetic direction, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra sounds refulgent in tutti, with a warm, firmly grounded sonority, and polished in smaller groupings, as in the symphony's first-movement development. The violins' rapid figurations sound thin, and their high phrases don't have an ideal sheen—there's the occasional hint of a whistle—but they're clear and well-tuned. There are brief patches of iffy coordination in the Rhapsody, in which the principal horn sounds slightly taxed at the peaks of phrases. The heavy brass register with a nice impact in Naxos's pleasantly ambient sonic frame.

|