|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 66

Notes of an Amateur: Lera

Auerbach, Stravinsky, Penderecki, Lutoslawski, David Matthews, and Jennifer

Higdon.

Auerbach. Celloquy. 24 Preludes; Sonata for Cello and Piano; Postlude. Ani Aznavoorian, cello. Lera Auerbach, piano. Çedille CDR 90000137. I've been waiting for this recording ever since I read of the existence of the music in the program notes of the CD of the composer's 24 Preludes for Violin and Piano. Russian American Auerbach is one of our most interesting and compelling young composers and I'm not alone in having high expectations for this release. To begin with, it's hard to believe any cellist could play this music, let alone one few of us are likely to have heard of. Shame on us. Ani Aznavoorian, principal cellist of the Camerata Pacifica and another of Chicago's best kept musical secrets, has a long resume of solo and chamber projects. She is a lights out musician whom I expect we'll be hearing a lot more about. She premiered this work in Hamberg and will be premiering Auerbach's Cello Concerto in 2013-2014. She plays with great feeling and exhibits formidable technical skill. The world is currently full of marvelously gifted cellists. Add one more. It took me three hearings to plug into this work, though now that I'm more familiar with it, you should take my slowness in picking it up as a criticism of me, not the composer. As these Preludes proceed, the music broods, laments, storms furiously, and rhapsodizes as it creates a deeply unsettled world. The cello is a powerful human voice using its full range to tell a disjointed, episodic, ultimately unresolved story. The piano, played brilliantly by the composer, is sometimes a full and powerful partner, sometimes a spectator. The work has baroque, classical, and romantic moments—and they are essentially moments—all woven into an exciting and complex modernist tapestry in which lyric passages are submitted to ironic restatement, dances given a manic haunting quality they can't seem to escape. We feel here that rather than the traditional masks of comedy and tragedy, we are faced with faces of romance and irony. Prelude 12, at the center of the work, presents this case explicitly. Auerbach uses the word "sardonic" to describe this music, and if we stand back from the 24 preludes as a whole, that word does seem to characterize it. Up close, it is rife with conflicting emotional textures—its 'day to day' quality is strikingly life-like. It is at a distance that we come to sense the rich, unresolved modern life it adds up to. As I wrote in talking about the Alexander Quartet's view of Shostakovich's Quartets, which they entitled "Fragments," this appears to be the way many of the best artists represent the world in our times. In a sense, 'construction' of some kind of whole vision from the parts must take place in our receptive minds and imaginations. This work will grow on you the more room and time you give it. Strikingly plaintive beauties glow out of the emotional dusk from time to time, notwithstanding the misgivings around them. Prelude 23 is a prelude-long example of this. We are told that the Finale, Prelude 24,recapitulates the themes of the earlier preludes, though my untrained ears couldn't swear to this. The Finale is full of wonderful clarion dissonant energy but creates no clearer vision than our original traversal, nor should we expect it to. We have heard the Sonata for Cello and Piano (2002) included on the disc played by its dedicatees, David Finckel and Wu Han on their own Artlistled label. This is the work that alerted me to the existence of Lera Auerbach and I remain grateful for it.

Stravinsky, Le sacre du printemps. Houston Symphony Orchestra, Christoff Eschenbach. Messian, L'assension. Houston Symphony Orchestra, Erich Bergal. Live recordings. HDTT. HDCD 261. It's not often that a 'state of the art' recording and a superb performance of music come together as they do in this spectacular release by HDTT of a 1987 live performance of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring by the Houston Symphony led by Eschenbach. And guess what? It's a 16/44 original! Meticulously transferred from digital masters by the people at HDTT who specialize in transfers of analogue to digital. All of which reinforces what recording engineer Da-Hong Seetto told me years ago: that it's not 16/44 that's the problem with CD's, it's what the manufacturers do with digital masters delivered to them. He expressed great disappointment to me at the difference between his digital masters and finished CD products. Anyway, this is one of the best recorded performances of the Rite of Spring I've ever heard, analogue or digital. Clarity, power, drama, and beauty combine to express the brutal inevitability that defines the work. "A terrible beauty is born." Stravinsky captures all of the mythic power in this line by Yeats about the rape of Leda by Jove that creates Helen of Troy and the Trojan war. Or, in Yeats' mind, the cruel modern world. The dancer dies to create the Rite of Spring, and Eschenbach and his forces get it all. Does the recording sound digital? Yes. Does it sound analog? Yes. The stunning clarity is digital, the rough and woody texture of the cellos and double basses and the reedy-liquid physicality of the woodwinds is analog. If recordings like this one, produced and manufactured in this kind and degree of clarity, were the rule they would have put to an end to the analog vs. digital, Redbook vs. high-res, etc debate years ago. It's not the medium, it's how well you use it. Own this CD to appreciate the state of the art of recording and to hear Stravinsky's masterwork as it is seldom heard outside of the concert hall. The Messian work is also very fine, both as performance and recording, but here it seems an encore, welcome, especially since most of us have not heard it, but a pure bonus.

Penderecki and Lutoslawski, String Quartets. The Royal Quartet. Hyperion CDA 67943. Krzysztof Penderecki's first two quartets (#1 - 1960; #2 -1968) belong to the experiments in texture stream of modernist music. Both works are short, full of percussive effects, and work on us like abstract paintings do. His Quartet No. 3 (2008), Leaves of an Unwritten Diary, is in the Shostakovich line, more concerned with narrative and emotion. Quartets Nos 1 and 2 are interesting, No. 3 is something we can get our teeth into. We are in the familiar world of Eastern European romantic sorrow crossed with dissonant counterpoint, the music of our time: musical experimentation has been left behind. This quartet is also more expansive and given considerably more time to be so. It indeed 'reads' like a diary and could easily have been broken into a series of movements rather than composed as a single one. That said, the transitions between individual musical statements work well, belying the shortness and ephemeral quality of some of them. Elegy, lamentation, a series of meditations. In less inspired hands it could all drift away. But Pederecki's hands are among the most inspired we have. Witold Lutoslawski, a generation younger than his fellow Polish modernist, wrote his single quartet (1964) around the same time as Penderecki's first two. It is a bit less spare but shares their aesthetic. It is reticent, laconic, cryptic—in two movements spread over 25 minutes plus. Apparently the four musicians have individual scores and are meant to play them essentially independently of the others—there is no combined score. Presumably—and we can hear this—the time signatures are the same, so the composer is able to maintain some control over the proceedings! This music—the whole school of which it is a part—is more interesting to contemplate than compelling to listen to, by intention. We have the feeling it was necessary, that music needed to play out some of the implications of earlier modernism. Perhaps strange to say, as detached as it is and encourages us to be, I'm glad we have it. But do come to it from nothing else. It works best in a world of its own. Shorter Notes

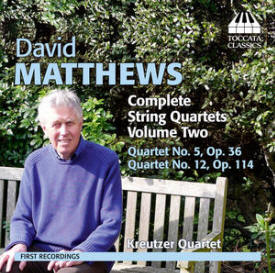

David Matthews, Complete String Quartets, Vol 1: # 4, #6, #10. Vol 2: #5, #12. Kreutzer Quartet, Cantata TOCC 0058, 0059. The world would keep turning and very few of us outside of England would notice if the music of David Matthews (whose brother Colin incidentally has written a very fine cello concerto) were not heard. I "noticed" it because I have a weakness for much of modern English music and am curious to hear what the generation after Britten make of him, or don't. T.S. Eliot was surely right in defining one of the major branches of modernism (his own) as new art that comprehends rather than rejects the tradition behind it. Britten's does that as does David Matthews' in its own distinct way. Not to imitate or sentimentally update the tradition so much as write music that has a new and creative place in it. I seem to remember reviewing some of Matthews' music earlier and enjoying it well enough. But his string quartets strike me as better than that. Matthews conspicuously loves stringed instruments and so the string quartet seems his natural medium. Begin with Quartet No. 10 (2001) in Volume 1 and work backwards. Don't go looking for startling, groundbreaking aesthetic innovation, just expect fine and sometimes eloquent string quartet music which explores and celebrates the genre. This music that his forebears would be surprised by but ultimately recognize and admire.

Jennifer Higdon, An Exaltation of Larks. The Lark Quartet. Gary Grafman, piano. Brian McMillan, piano. Todd Palmer, clarinet. Bridge 9379. Contemporary American composer Jennifer Higdon is a handful. Modernist, though not aggressively so, occasionally almost heartbreakingly lyrical. She wanders where she wishes. Her Piano Trio (2003) gets played a lot around the Neill house. So will the clarinet quartet, Light Refracted, and piano quintet, Scenes from the Poet's Dreams on this new CD, featuring the Lark Quartet and a couple of visiting musicians, including well known pianist Gary Graffman. Higdon is often a modern impressionist. She sees herself as playing with sonic impressions of light, which is neither here nor there but clearly seems to lead her a place related to the one Debussy went to. Her light, which changes quickly and often, is more reflected and refracted than his, which is her principal musical distinction. Equipment used for this audition: Resolution Audio Cantata CD player; Crimson CS710 preamplifier and CDS 640E mono-block amplifier; Tocaro 40D loudspeakers; with Crimson cabling. Bob Neill, a former equipment reviewer for PF Online and For the Music, is also proprietor of Amherst Audio in Amherst, Massachusetts, which sells equipment from Audio Note, Blue Circle, Crimson Audio, JM Reynaud, and Resolution Audio. He is also a sales agent for Tocaro loudspeakers distributed by Austin (Texas) Hifi.

|