|

You are reading the older HTML site

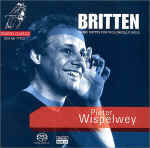

Positive Feedback ISSUE 7 Benjamin Britten, Suites for Cello, Pieter Wispelwey

An appreciation for (most of) the music of Benjamin Britten requires a taste for the artistic expression of pain. That, of course, is the secret of tragedy, and Britten wrote a few of those (with help from Melville and Henry James), but it is also true of art that captures the smaller, though no less intense pain of disappointment and longing. This is not pathos—which has its own artistic genres that tend to live on the romance racks or on country music stations—but a more particular pain, requiring subtler and more exquisite artistic definition. Britten wrote a great deal in this vein, and his cello suites are among his finest. Though his personal instruments were the viola and piano, the instrument he wrote most effectively for (aside from the male tenor voice, Peter Pears' in particular) is the cello. Some find his Symphony for Cello his most powerful instrumental work, and I can't argue with that, but the three suites he wrote for friend and musical colleague Mstislav Rostropovich—the Symphony was also written for him—are, in their sparer way, equally compelling. Rostropovich's Decca recordings of Suites One and Two (he has not recorded the Third, which was written just before Britten's death) are extremely moving. They marry Rostropovich's tragic imagination to Britten's, resulting in something nearly as Shostakovian (I am thinking of the quartets) as Britten-like. I was not so much aware of this until I heard Pieter Wispelwey play them differently—all three at one sitting—at the Longie School. This was twelve years ago, about the time he recorded all three for Globe (nla). A year or so ago—thanks in part, I presume, to the generosity and artistic intelligence of Jared Sacks—Wispelwey revisited the Britten suites for Channel Classics, and it did so well that Sacks has chosen to re-release them on SACD. Comparing CD and SACD recordings of a solo instrument is a wonderful way to hear exactly what's going on with this new format. I will get to the CD/SACD comparison in a moment, but I expect that, to most readers, the differences between Wispelwey's and Rostropovich's approaches to these pieces are at least as interesting. The Russian is more plaintive, introspective, intense, and alone, although, oddly, his timings tend to be shorter than Wispelwey's. Focusing on the 'Lamento' movement, which strikes me as representative, Rostropovich's cello wails, recalling—though in a quieter voice—fellow Russians Kanchelli and Sophia Gubaidulina in the latter's Canticle of the Sun (also written for Rostropovich, and recorded by him on EMI). Wispelwey's "Lamento" hasn't Rostropovich's tragic cast. It is more stoic, and the young Dutch cellist brings out more of the music's contrasting moods. Wispelwey plays Hawthorne to Rostropovich's Melville. Which of the two comes closer to Britten's sense of this music is an interesting biographical question: Is it the older man, who knew him well, or the younger man, who likely never met him? As with all truly great music, different performers of the Suites can express different conceptions of what they are about. I wouldn't be without either. (The Rostropovich recording is not available in the US, but can be ordered from www.mdt.co.uk. Revisiting Wispelwey's earlier transversal of the suites on Globe, I found them more pensive than the new ones, with still longer timings. Meditative, expansive, and thoughtful, though less intensely focused than the 2001 performances, they represent an even greater contrast to Rostropovich's sense of this music. Comparing the Channel performances on CD and SACD, the latter immediately struck me as more beautiful—more finished and refined, but with no less drama. Wispelwey sounds like a more polished cellist on the SACD. In several passages, the lyricism he strives to set against the suites' darker moods is more successfully achieved on the SACD. Notes are not as blunt on the pizzicatos, and seem to last a little longer. The venue is larger, more apparent, or both. As I said in the comparison of Rachel Podger's Vivaldi Opus 4 CD and SACD, the CD sounds fine, and nothing appears to be "missing," but the SACD is more appealing. This appeal is addictive. I found I did not want to give it up and return to the slightly coarser, seemingly less tranparent CD once I'd been with the SACD a while. Both the Podger and Wispelwey SACD's were recorded in DSD. According to Sacks, all Channel Classics available in SACD have been recorded in DSD. The improvements I heard on the Wispelwey are just as obvious as they are on the Podger recording. Once again, the coarse/fine grain analogy comes to mind. The fineness of grain on the SACD does not feel like an artificial smoothing. It feels like a closer look, a more lifelike representation of a performing cello. A recording of a musical instrument (the harpsichord is the most dramatic example) never sounds as appealing as the real thing. There is an inevitable hardening that vinyl seems to soften and that digital audio designers fight to overcome with various sweeteners, including tubes. With this SACD recording, the cello is as appealing and real as I've ever heard on record. More of what I love about cellos seems present on this SACD, suggesting that the new medium does in fact represent progress. It will be interesting to see how persuasive this degree of progress is to the world at large, and whether it is allowed to flourish before the next breakthrough arrives. System for review: Audience modified Sony NS999ES DVD/CD/SACD player, Blue Circle AG3000/8000 electronics, Reynaud Concorde speakers, Audience Au 24 interconnects, Au 24 and Reynaud HP216A speaker cable, Elrod EPS Signature power cords. |