You are reading the older HTML site

Positive

Feedback ISSUE 74

75 YEARS | 10 YEARS

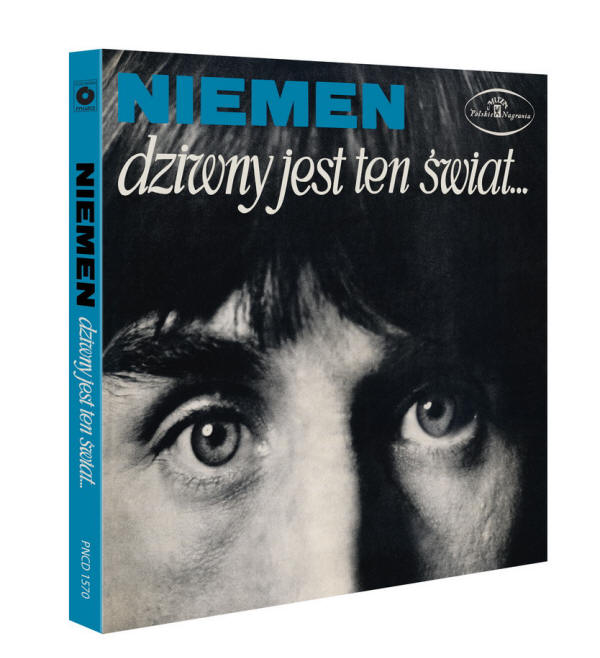

It would be difficult to imagine a better combination of topics that work well with my lifestyle than the current edition of High Fidelity you're reading right now. It combines three things that complete me, make me full. It's an "anniversary" edition of a magazine founded by me 10 years ago, a magazine that allows me to do what I love the most. Which in my case means listening to and writing about audio components and music itself. And getting paid for it. HF is a Polish magazine but it's also published in English and it's well-recognized beyond our country's borders. The current issue is also a "Japanese" edition dedicated to components from the country of cherry blossoms. For years, May, or the month of HF's birth, has brought you reviews of products manufactured in the place where audiophilism and music go hand-in-hand like religion. I admire the people who make CDs and audio components there, because if they're worth checking out, they're amazing at what they do. And, last but not least, this edition's cover and editorial are dedicated to something absolutely Polish, yet timeless and international: the album Dziwny jest ten świat… (It's a strange world…) by Czesław Niemen. The subject has been prompted by this year's 75th anniversary of the artist's birthday, and the corresponding re-release of the aforementioned album. But at first, it didn't go quite easily hand in hand. Japan and Niemen—I was certain of those two things. I did, however, fight with myself over what this editorial should really be dedicated to—would it be better to honor the anniversary by writing some memories and anecdotes, nostalgically listening to the voices of the readers and my own, wallowing in the light reflecting off their eyes?... I was sobered up by the story that revealed itself after my conversations and interviews I conducted while preparing for the article about Niemen's album. I first exchanged emails with Ms. Małgorzata Wydrzycka who takes care of the artist's posterity, directing the Czesław Niemen Foundation. They helped me pick up pace with my quest, which resulted in interesting, in my opinion, effects. And there's no competing with a man like this, a story like this, and music like this.

Is there anything I could say that High Fidelity's readers don't know yet? That the idea for this magazine didn't come to me, but to my wife? That for half a year I searched for a man who'd be able to turn my ideas about an online magazine into reality (if anything that's online can even be considered reality)? That initially nobody in Poland understood the combination of the words "online" and "magazine", and even nowadays they cause some skeptics to characteristically raise their eyebrows? I could say that ten years of existence translates into tens of thousands of readers every month, the recognition of the magazine in Poland as well as abroad, the cooperation with some of the largest audio magazines from all over the world, and, finally, readers' trust. Even that wouldn't be much of a discovery. That's why I leave stories like that for meetings for leisure and pleasure, over some beer, music, and tweeting birds. Because nothing can really rival music being played back in the best possible way, and people who stand both behind the recorded material and the audio products thanks to which the material is resurrected, risen from oblivion; because music that isn't played or music that's played back very sloppily, is only hypothetically alive. My ambition was for High Fidelity to be a point of reference, as transparent as possible, through which music and equipment used to reproduce music would shine brilliantly. I thank you all for these past ten years. I thank the readers, the dealers, and the manufacturers. You are the ones who have created this magazine. Without you, there wouldn't be any of this. CZESŁAW NIEMEN Dziwny jest ten świat…

This article is neither the history of the creation of the album, nor is it even the story of Niemen himself. There are publications that do a good job of describing his life and works (check the sources section at the bottom of the article). I'm not interested in gossip, especially of the kind that isn't supported by facts from Niemen's biography. My goal is to present to our readers a physical manifestation of a piece of Niemen's work—his debut album, in all of its possible forms (except the cassette tape). I'm interested in the way that the sound, and the cover art, had changed over its different editions. It's supposed to be an open project, therefore I'm counting on your corrections and additional input. I'm guessing that most of the readers think this is less important than the music itself. But please think about this again—a musical piece lives on three levels: in the sheet music, in its realization, i.e. performance and in the recording of a particular rendition. In the case of popular music recordings, the two latter levels are synonymous—the disc release is also the original release. Each alternative rendition of a given song, be it by the same artist or by someone else, is secondary. Therefore it's accepted that the first release is the original one. The ones that follow, including re-masters, are repetitions, or actually attempts at re-interpreting the original. It's a different case than what you get in literature or art, where the original piece is the last one published during the artist's lifetime, with their permission and under their supervision (in literature), or the final version completed by the artist (in art). When it comes to music albums, we deal with a situation where the end effect changes constantly, and the sound is corrected and changed, whether with the artist's (or band's) help, or without their knowledge and approval. Let's not be fooled—sound is an inseparable part of a musical piece, regardless of what form and medium it's released in, even if it's just an audio file. When it's changed, the piece itself is changed. For good or for worse. That's why the differences between various releases of Dziwny jest ten świat… are so important to me. They were also very important to the artist himself, who cooperated in, and even produced three out of five currently available digital editions of this album. The basic goal for me was deciding in what way the 2014 remaster modifies Niemen's vision and whether it's closer or further away from the original—the first vinyl edition from 1967, and on a wider plane – how that relates to the sound of other releases from that time period. To get a full picture I bought all of the (legal) re-releases of this album, both vinyl and digital (Compact Disc). It wasn't really a big problem, although finding the original edition from 1967 in good shape, i.e. the one without the "Golden Record" sticker, with a thick layer of paint on the cover, proved to be quite a challenge. But it wasn't impossible. I also managed to find a fairly good-looking and well-sounding so-called "four". I wasn't, however, able to find the debut edition with both of the stickers on it—the "Golden Record" and "1st Place At the Youth Record of the Year Ceremony 1967". There were no problems with getting the digital versions, although the first Digiton edition is quite expensive. All in all, we're dealing with six vinyl versions and five CDs. Initially, this article was meant to be no longer than three A4 pages. It ended up being 19 pages long in small print. I know that people tend not to read long articles anymore, choosing instead compact "cheat sheets". But I do believe that if something interests them, they're capable of dedicating themselves to it—I hope that will be the case with you and with this description. I encourage you to set apart some calm reading time, make yourself some good tea or coffee, pour yourself a glass of something, and play the album that I'll be talking about. I invite you to this audition and discussion about Czesław Niemen's album Dziwny jest ten świat….

GOLDEN RECORD Związek Producentów Audio-Video (Union of Audio-Video Producers, UAVP), formed in 1991 at the initiative of musicians, music producers and journalists, has the statutory goal of representing producers and fighting audio piracy. Aside from these main goals the UAVP is also supposed to promote publishers and artists through giving the Golden Record award. The information from 2013 says that to win it, a Polish artist (performer) must sell 10,000 copies (it was 20,000 until 2005). Actually, this number doesn't only include sold copies, but also returns and warehouse leftovers. When the award was introduced in Poland in 1968, this kind of low threshold would've resulted in pitiful laughter. Until 1972, to receive the Golden Record award you had to sell at least 125,000 LPs or 250,000 SPs or the so-called "fours" ("Wikipedia" says 160,000 and 250,000, respectively, and the leaflet inside the 2014 re-release of Dziwny… mentions 100,000 of the former). The first Polish artist to receive this award on December 20th 1968 was Czesław Niemen (February 16th, 1939 – January 17th, 2004) for the album Dziwny jest ten świat… (Polskie Nagrania "Muza" XL 0411; the cover says: dziwny jest ten świat…; I'm only adding the capital letter at the beginning, while keeping the ellipsis, omitted by most publications) released a year prior.

Czesław Juliusz Niemen-Wydrzycki, born in Stare Waliszki, a village currently located in Belarus, repeated this success in 1970 (for the album Sukces from 1968) and 1971 (for the album Enigmatic from 1970). Out of the 91 Golden Records awarded until 1988, three of them have been given to Niemen (information from Złote Płyty w Polsce Ludowej: 1968-1988, see HERE). The tracks on this LP debut album, recorded in the spring but released in the autumn of 1967, were known earlier. For example, the title track comes from the days of Niemen's Paris adventure of 1966, and Gdzie to jest? comes from the artist's first period of musical activity in 1963. The recording session took place from April 12th to 15th, 17th-18th as well as April 20th,1967. During this period the Artist recorded twelve tracks that appeared on the album, as well as three extra ones: Jaki kolor wybrać chcesz, Proszę, przebacz and Domek bez adresu, released later on the so-called "four", i.e. a 7" 45 rpm single containing four tracks, signed with Niemen & Akwarele (Polskie Nagrania "Muza" N 0497). The fourth track was Dziwny…. Niemen's photographs are an inseperable part of his history. He's been photographed by the greatest, including Marek Karewicz (born 1938), who was quoted at the beginning, as well as his older late friend Władysław Pawelec (1923-2004), who is the author of photographs on the artist's first three albums, including the seminary close-up picture of Niemen's eye on Sukces, his debut album. The career of Mr. Pawelec is an example of what an amateur who is passionate about what he does can achieve. His career path was actually medicine. He studied at the Medical Academy in Lublin which he started before the break of World War II and managed to complete three years of his education before the war began. After the war he worked in a research-development lab. He quickly started achieving success in this field—in 1952 he got the National Award of the 2nd rank, in the Technical Progress Department, for starting the production of the anti-rheumatism drug, A.C.T.H. He moved towards photography through his work—between 1954-1964 he worked at the Institute of Serums and Vaccinations, where he did a lot of technical photography. Two years later he became a member of the Polish Photographers' Union and began publishing his photographs in the travel magazine "Światowid". In 1976 Władysław Pawelec was in a car accident that forced him to take a year's break from his work. This break had a positive influence on his career, though, because shortly after that he became independent and opened his own photo studio in Warsaw. Among his clients were some of the greatest artists of the Polish scene: Wojciech Młynarski, Czesław Niemen, Czerwone Gitary, Katarzyna Sobczyk, Karin Stanek, and Izabela Trojanowska. He's also very well known for his erotic photography, which he largely pioneered in Poland. Władysław Pawelec was the author of the photos for Czesław Niemen's Dziwny jest ten świat… (1967), Sukces (1968) and Czy mnie jeszcze pamiętasz (Do you still remember me,1969; with Leopold Dzikowski). Mono Dziwny jest ten świat…, Czesław Niemen's first album, is only available in mono format. It's kind of a weird story with this mono. In the time that it was released, the albums issued by Polskie Nagrania "Muza" always had two codes on their covers: XL 0866 and SXL 0866. These are the codes on Nowy wspaniały świat by the band Dwa plus Jeden, engineered by Zofia Gajewska who was also responsible for two of Niemen's albums: Enigmatic and Człowiek jam niewdzięczny (An ungrateful man am I, 1970). The first of the two codes denoted a mono disc, and the second one stood for stereo release. In those times LPs were still being released in both versions. Try thinking of the history of The Beatles' records, where all the way up to the 1968 album The Beatles, the first edition was always released in mono and it was these mixes that were supervised by the band members who left the stereo mixes in the hands of George Martin, without paying too much attention to them (see HERE). The first and second editions of Dziwny jest ten świat were released in mono. The third one, however, with a "banana" inlet, was marked SX 0411 and "S33", which definitely meant a stereo record. The sound on this disc is undoubtedly mono, however.

But as far as the Beatles thought of stereo as a "toy", Czesław Niemen saw its potential and a chance to realize some of his ideas. A fragment of an interview that the artist had with Wiesław Królikowski, the editor-in-chief for "Tylko Rock" magazine (currently named: "Teraz Rock"), shows just how badly mono sound irritated him. Attention: this fragment is from the version of the interview which was later published by "Pamietam.ovh.org", as it has been deleted from the version of the interview available on "Tylko Rock" webpage: I listen to what it was like with those engineers during the recordings… We did get into some heated discussions. For example, the sound engineer, Ms. Jastrzębska, had her own vision of the story. She'd say: why is that snare drum here, it's interfering! And I'd say: it's meant to be here, because without it there is no music of this sort! (laughter). And we'd start arguing. In the end I'd end up waving my hand at her dismissively and engineering the album the way I wanted to. Some very poor recordings were produced due to that kind of atmosphere… The albums Dziwny jest ten świat, Sukces, Czy mnie jeszcze pamiętasz could've been stereo, but they simplified it. Ms. J. looked in the funny device for checking mono playback. And she concluded that once they mix down the stereo, it'll be no good… There were constant struggles. In some of the recordings there was a "wooden" bass, but when you added some lower tones, the bass would turn boomy and blur out the rest. And now [i.e. while preparing the two box editions of Niemen od początku - editor's note] I lost a lot of time trying to fill in whatever I perceived to be missing in the frequency response. Niemen - przekora uniwersalna, (Niemen – universal defiance) "pamietam.ovh.org", see HERE; Wiesław Królikowski, Niemen: przekora uniwersalna, "Tylko Rock" magazine, April 1st 1997, see HERE.

Details like this were incredibly important to the musician who became famous for yelling: "Could the sound engineer please amplify the microphones as much as you can, I'll do the mixing myself," at the V National Festival Of Polish Songs in Opole (1967). He was a perfectionist. The possibility of going where he dreamed of would only open up many years later, in the "electronic" period, when he controlled the tracks from beginning to end. And he really needed stereo, as shown by the following fragment from the same interview as before: My first "Latin American" songs were recorded by professor Karużas, who had an amazing ear. That's an understatement: he sure had good taste! And just imagine that those recordings from 1962 turned out to be stereo, although on the single, of course, they ended up in mono. I had least problems with those songs… Same with Lekcja twista, which I was very ashamed of back then. Part of the reason was the poor sound of the vinyl, thin and lacking proper frequency extension. And in addition I sang there with that thin voice of mine (laughter). But when I got the master tape, I decided that the instruments sounded very good. And it was also recorded in stereo! I just added some equalization to clean out the noise. And I think it's pretty good. Wiesław Królikowski, Niemen: przekora uniwersalna (Niemen, a universal defiance), "Tylko Rock", April 1st 1997, read HERE. His dream only came true with the release of Enigmatic, his first truly stereo album. The degree to which this annoyed him can be seen through Niemen's personal decisions while working on his self-edited re-releases of Dziwny… as part of the Niemen retrospekcja series from 1995 (Digiton DIG nae 101) and Niemen od początku II from 1996 (Polskie Nagrania "Muza" PNCD 358). Both of these releases were prepared using a pseudo-stereo effect. This technology had been known nearly from the very beginning of stereo, and it was based on electronic processing of the material in a way that artificially made the sound more spacious. It has been described in many different ways. For example, the 1966 re-release of Frank Sinatra's album My Cole Porter is marked as: "Electronically Enhanced For Stereo" and a special "Duophonic" logo was used. What's interesting, this type of treatment was mostly used in re-releases—Sinatra was released in the Pickwick Series, a repetition of the original. The achieved effect didn't appeal to everyone and today it certainly doesn't earn enthusiasm, either. Perhaps this is why Niemen quit the effect of sound "widening" on his 2002 box edition, Niemen od początku I (Niemen from the start I, Polskie Radio PRCD 353) Ms. Eleonora Atalay, musician's daughter, and Mr. Jacek Gawłowski, responsible for the sound of the latest re-release of Dziwny jest ten świat…, released on the 75th anniversary of Czesław Niemen's birthday, have turned even further away from that effect. "Remaster 2014"

This release has been prepared with extreme care. I'll go into detail while describing its sound and I'll point to the elements that other companies, or Japanese masters, do even better, or different. But there's nothing to be ashamed of. Quite the contrary—although you can discuss certain choices, it would be a discussion about certain assumptions, and not about the quality. The idea for this edition seems to have come from the record label, Polskie Nagrania. Ms. Anna Grzywacz, Chief Project Specialist, was responsible for this project. I asked her about a few basic things. Wojciech Pacuła: In the promotional material, you mention that it's the first album in a series—what are the plans for the following titles? Anna Grzywacz: We're planning on releasing all of Niemen's albums which had their original versions published on vinyl and were released by Polskie Nagrania. The next release will be the album Sukces which we are currently working on. All of the albums will be released both on CD and vinyl. Dziwny jest ten świat… had its "vinyl" premiere on March 28th. Both re-releases were prepared by me. Is the label considering preparing a special "box" for the albums? I think we'll be making that decision closer to the finish. The whole process of preparing these releases is long and labor consuming in all of its phases, beginning from de-noising and remastering, and ending with editing and printing. Where is the vinyl pressed and who's responsible for its preparation? Repliq Media takes care of CD and LP manufacturing to http://repliqmedia.com. The latter statement was very interesting. Repliq Media specializes in the manufacturing of physical audio media, as well as cases, prints, books with attached CDs that have recently become quite popular, and, finally, vinyl records. As Mr. Dariusz Lutomski, the owner of the company, says, a large part of their work are projects released in small numbers of copies, new musical projects, album premieres and new bands' debut releases, which begin with budget editions—samplers. They're not usually mass-production but rather collector's editions, and—as he calls them—they're refined and made "noble", literally and metaphorically. "Every projects needs its own special treatment and care, which is absent in mass production." And then he adds: The people working at Repliq have a lot of experience in music industry and especially in dealing with demanding customers who care about high quality and originality, which means a lot of new challenges every single day. I started working in this field myself when the cassette tape was still the king and I witnessed the rise of CD and DVD production in Poland. Cassette tapes started vanishing, rapidly replaced by CDs, and now I'm looking at the demise of that format and the rebirth of analog media. All of this happened in a relatively short time, but all of the aforementioned formats will still function on the market and each will have its own dedicated fan base. Because of this, there's quite a bit of strong sentiments and nostalgia in our work, which means that projects such as the re-release of the album you're writing about, brings us a lot of pleasure. I'll use this chance to brag about our office's "entertainment center" (you can see a photo of it on our social networking page). I reactivated my vintage AKAI AP-002 turntable, a model from the mid-1970s, if I remember well. I paired it with an old Brandt QX3535 amp, an export product from Unitra. You've got to admit that getting your dream LPs doesn't require queuing for hours anymore :) Coming back to your questions, the mastering of this particular album is the work of Mr. Jacek Gawłowski. Regarding your question about the pressing plant, I unfortunately have to decline answering it as it's classified information. I can only say that we cooperate on a daily basis with a few different pressing plants around Europe. They are currently loaded with work, which unfortunately negatively impacts our cooperation. But that happens—sometimes you have to tread hard to make a path to your supplier and eliminate the bad partners. In my experience, and based on our customers' opinions, proven pressing plants really don't differ much when it comes to quality. Most vinyl records that we order are 180g black discs, offering the highest quality. Re-mastering has four hands

Mr. Jacek Gawłowski, mentioned by Mr. Lutomski, is a key person to the latest release of Dziwny jest ten świat along with Ms. Eleonora Atalay. Since he was "called out" first, I'll start with him. His "natural habitat" is the mastering studio. He's been involved in mastering numerous albums, but there's one that really stands out: the mix of Włodek Pawlik's Night in Calisia, which he recently received a Grammy for. He's a sound engineer and audio producer that began his career at the end of the 1980s as a guitarist. In 1994 he graduated from the SAE Institute in London. In the 1990s he made himself known as a recording engineer, but the following decade changed the direction of his work. That's when he started his own studio and mastering company, JG Master Lab. His clients back then included artists like Ania Dąbrowska, Sistars, and Anna Maria Jopek. In 2008 another studio was founded, which he equipped with the legendary SSL mixing console. Starting with that moment, mixing became Mr. Gawłowski's main occupation. The artists now included Kayah, Aga Zaryan and Randy Brecker. The year 2012 brought the new iMix studio and the continuation of his current work. It was also when he cooperated with the band T. Love while mixing their album Old is Gold, which was also released on vinyl. This album received the Fryderyk award in the "Album of the year" category. A few simple words with… JACEK GAWŁOWSKI | iMix Mastering and sound engineer, studio owner Wojciech Pacuła: Could you please tell me about your part in re-mastering Dziwny…? Jacek Gawłowski: My role was transferring the material from the original analog master tapes into the digital domain, in high resolution, as well as re-mastering the recordings. How the work was divided between you and Ms. Eleonora? Ms. Eleonora took care of renovating these recordings, while I worked on their sound. What was your reference point? The point of reference for my work was my own taste, preferences and experience. I also knew the sound of the original vinyl LPs, but I also wanted to improve the quality of what was on the tapes, as well as delicately bring out some subtle details. Please tell me, what was the condition of the original master tape—did you get the original session tape, or a copy? Are there different versions of it, e.g. a stereo version? I got the stereo originals. The tapes from the 1960s weren't always in best shape. There were some dropouts in the channels, some crackle, and that's what required Ms. Eleonora's special attention. Could you please repeat that, because I think I misheard you—you received a stereo master tape? Yes, the original tapes were in stereo. However that stereo is actually mainly the "return" of the 'plate reverb' effect. I don't understand why it was mixed in such a way that the instrument panoramas are in mono, and only the 'reverb return' is stereo. Pretty much all of Czesław Niemen's solo albums from the latter half of the 1960s have been mixed this way. It has its own charm, and the additional upside of this method is its 100% compatibility with radio/TV, because radio and TV only emitted mono sound back then. You're mentioning A/D converters as if they were particularly important to this process—what did you use? What other tools did you use? For the transfer, I used converters manufactured by Apogee, the Symphony model. I ran some tests with them and they turned out to be most transparent of many converters. The album was then remastered in the digital domain, using equipment from Weiss Engineering (EQ1 and DS1). What were you aiming for, as in, what were your goals? I'm asking because the artist's personal vision regarding what his record should sound like is known to the public. Meanwhile, the new remaster is quite different. My vision wasn't to radically change the sound of these recordings, but to delicately correct it. I think I have been successful with that. This remaster has been well-received by the artist's fans and by audiophiles. It was all about an attempt at taking the piece created several decades ago and moving it into the present time in the least possible invasive way. The remasters that Czesław created himself in 2003 were an attempt to radically change the sound of his works. Such was his vision, and that has to be respected. What's the role of the person responsible for remastering? What should be his reference point? The original release, the last version prepared with the artist's input, or something else completely? Every anthology is a different mastering challenge. In Czesław Niemen's case, we're dealing with songs that entire generations have been raised with. The original vinyl records and analog tape source material should be the reference point here. What system do you use to listen to recordings? I use the L-707 speakers from Lipinski Sound with two subwoofers and amps from the same company. (Andrzej Lipiński, a Pole, the founder of Lipiński Sound company, has chosen the slogan "Timeless Analog" for their webpage, which is an important move – Ed. note) What kind of signal was used to cut the vinyl? Who did the mastering? The same mastering I did for the CD was used to produce the black disc. The pressing plant received 16-bit 44.1kHz WAV files. There was no further interference in the sound from that point. The conversion during the transfer was made with the Apogee Symphony. There was no point in sending the material to the pressing plant on a master tape because it would mean an additional D/A conversion. These days pressing plants prefer working with wav files. Did you also prepare the recordings from the "four" that made it onto the previous digital releases? I did. I remastered the "four" that contains the song Sen o Warszawie, among others. Will it be released? I don't know. Will you also be working on Niemen's following albums? This one is amazing… Yes, apart from Dziwny… I also re-mastered the aforementioned "four", as well as Sukces and Czy mnie jeszcze pamiętasz. Will you also be working on the other albums? Probably not—I don't know who will be responsible for the remaining albums.

In terms of differences between mastering and remastering, the former term is used to describe the process of creating a master, which involves transferring recorded audio from a source containing the final mix to a data storage device (the master). The source material is processed using equalization, compression, limiting, noise reduction and other processes. More tasks, such as editing, pre-gapping, leveling, fading in and out, and other signal restoration and enhancement processes can be applied as part of the mastering stage. During the mastering session each track on an album receives the final adjustments that are needed for different playback media, such as vinyl or CD. Each medium requires special equalizing, balancing and other processing steps to fine-tune material for release. Remastering is the process of taking an existing master and mastering it again. It may refer to the process of porting a recording from an analog medium to a digital one, but this is not always the case (source: Wikipedia, Audio-mastering, Remaster). Things are no different when it comes to re-releases of Niemen's albums—a 're-release' is often used interchangeably with 'remastering', meaning the act of "cleaning out the sound", as musicians put it. As I've already mentioned, two people are responsible for the new editions of Niemen's works—Mr. Jacek Gawłowski and Ms. Eleonora Atalay, Czesław Niemen's daughter. The work distribution between Mr. Jacek and Ms. Eleonora was also a division of competence. During the first phase the owner of the iMix studio took care of transferring the signal from an analog tape to the digital domain, in high resolution. The material was then sent to Ms. Atalay who began "cleaning" the recordings of noise, crackle, and drop-outs, due to the imperfections of the original tape. I think this part of the work can be called the "renovation" phase. The corrected material then returned to Mr. Gawłowski who began working on tonal and level correction, etc. I'd like to point out that only the combination of all of the aforementioned elements can be considered a true "remastering". My own experiences confirm that. We already know something about the first and third phase. Now it's time to learn a little more about Ms. Eleonora Atalay's part in the preparation of Czesław Niemen's album. A few simple words with… ELEONORA ATALAY Vocalist, record producer

My interviewee has graduated from the Karol Szymanowski music school in Warsaw. For six years she's been playing the piano as her main instrument, which was replaced by the oboe in the last two years. In high school she became a vocalist of a funk band called "Osmesmake", which performed in Warsaw clubs. At the same time she toured with Natalia Kukulska as a choir singer. Straight after graduating from high school, Eleonora Atalay left Poland to attend Byhřjskolen school in Ĺrhus, Denmark, where she sung in a Latino band and enrolled in Emagic Logic (currently, Logic) musical arrangement program classes. By the end of the 1990s, Eleonora could be heard during Natalia Kukulska and Wojtek Pilichowski concerts as well as on their records. She was also offered work with Piotr Szczepanik and Andrzej Piaseczny "Piasek". She was performing song covers in Warsaw clubs. In 2002, Eleonora released her debut album, still under her maiden name Niemen. The album consisted of her own compositions to which she also wrote the lyrics. Rafał Gorączkowski, a musician from the band "Goya", assisted in a few compositions and produced all of the songs. The album's single Kochać będę (I will love) held its spot in MTV Poland's top 10 for a long time, reaching No. 3. After Czesław Niemen, Eleonora's father, passed away in 2004, she decided to become a sound engineer to help with archiving and issuing his heritage. In 2006, she attended an intensive sound engineering course in London, which lasted for a year. Before remastering her dad's classic albums, she worked on restoring the sound quality on the Polskie Radio release of Czesław Niemen's 41 Potencjometrów Pana Jana ("Mr. Jan's 41 potentiometers"). Working on Kattoma/Pamflet na ludzkość ("Kattoma/Pamphlet on humanity") and Pamiętam ten dzień ("I remember that day"), apart from sound quality restoration, she was also involved in remastering under Ewa Guziołek-Tubelewicz's careful eye. Currently, Eleonora is working an Antologia that will be released by Polskie Nagrania. She's also a member of the supervisory board of The Czesław Niemen Foundation, where she promotes her father and his work along with her mother, Ms. Małgorzata Niemen, and her sister Natalia. Wojciech Pacuła: Where did the idea of a re-release come from? Eleonora Atalay: The main reason was the fact that there hasn't been any edition of that sort, and it turns out there should be. Whenever I managed to find a CD with the material I knew from vinyl records, I was ecstatic. It's really convenient to be able to listen to my favorite songs while I'm on the bus, for example. At one point I realized that my dad's masters are so personal they actually are very different from the originals. I thought to myself that it's high time to issue proper digital releases. It turned out that the record label, Polskie Nagrania, is also interested in such a re-release. Please note that the cover art in this edition is basically identical to that of the first vinyl record, similarly to my dad's project, Niemen od początku. We all truly cared about conveying the spirit of the 1960s in both the sound and cover art on this edition. All of the available legal digital versions were always based on my dad's original vision. He himself was saying that he always cared about improving everything that he thought to be poorly produced on the original release. Such an approach is completely understandable to me, however one cannot deny the fact that these recordings go back to the 1960s, when different rules applied. Moreover, people were used to this older version rather than what my dad proposed on Niemen od początku. To be honest, I was also guided by my own expectations. I remember when I managed to buy the CD version of Michael Jackson's Of the Wall, the album that I had been constantly listening to as a kid, and expected identical auditory sensations to those I remembered from the vinyl. After playing the CD, the album seemed much "colder" and "harsher". As a result, each time I listened to the CD my brain had to make up for the missing musical information that I remembered from the analog sound of Jackson's songs. What did you find needing improvement on the previous edition, the Niemen od początku box set? The new remaster is an attempt to faithfully reconstruct the original, rather than to improve anything. The main premise was to minimize any alteration of the original recording. My dad, in turn, always aimed for the kind of sound that he favored at a given time (please note that he remastered the album Dziwny jest ten świat three times). His goal was to improve on what was already there, ours—to bring it back. The box set was personally prepared by Mr. Niemen, including the A/D conversion (first 20/44.1, then 24/96) and mastering. Do you know, by any chance, what did it look like? What kind of equipment was he using? What was important to him? Dad was always trying to use the best equipment available. The order is always the same. After converting an analog recording to a digital one, a new quality is established. My dad worked that way, too. It's difficult for me to describe it in detail. From what I remember, he approached every song, each composition and every problem individually. He did not look back to the original at all. He concentrated on getting out the most of a recording "here and now" for his own artistic satisfaction. It was the same way with everything he'd ever done. I believe that these two box sets remastered by my dad in the last two years of his life are important not just because they contain his work. To me, as a person who works with the sound professionally, it's a documentary about what Niemen heard and created in this final stage of his life. I think it's a release that has a lasting value. However, it's impossible to understand what Niemen was trying to achieve with his last remaster, and how he referred to the original, without listening to the new re-release. What's also worth noticing is my dad's approach to editing the old photos that came with the box sets. Please note that the colors are retouched and there are many abstract elements included in the cover art design. This colorful world that my dad decided to breathe into the black and white picture reflected his vision that was also present in his remaster, which he finally decided to present to us. You write about noise reduction—I understand we're talking about digital noise reduction, yes? What does such a process look like, what tools do you use and what, in your opinion, is worth sacrificing (since nothing comes for free) in the process? Yes, noise reduction is a process carried out on a digital version of a recording. Regarding compromises – every process results in addition and subtraction from the general sonic image, which is why every interference with the original should be thoroughly thought through. I think we've lost so much time not appreciating the potential and quality of vinyl. When people were presented with a small, barely visible, low resolution digital medium, it became clear that such convenience came at the expense of sound quality. The process of noise reduction may be done poorly or it may be done well. If done correctly, the process involves reducing the background noise of the music material without eliminating the actual sonic elements. There's a variety of noise-reduction software available on the market. I'd recommend trying out some and deciding on the one that functions properly. I believe that all noise that may interfere with or does not belong to the sound of an instrument should be removed. I also think that minimizing the interference with sound waves is crucial to obtaining a good result. In short, a thorough diagnosis of the problem and leaving flawless areas untouched. To be completely honest, the process of noise reduction is nothing compared to the reduction of other types of short-time or peak distortion. The latter requires an even more thorough and time-consuming approach. There are many engineers out there that do not deal with this kind of distortion reduction, as there simply might not be enough money for it in the budget. I've also encountered an explanation that this process uncovers a whole new level of distortion. I disagree with that though, as we live in times of miracle-working plug-ins. There are also sound engineers who save time by reducing noise along the whole track length instead of focusing on short, one millisecond long cracks that are located in distant spots along the track. In the former case, the whole track is processed which results in a kind of stocking-like veil over everything (like putting on a photo filter). As I've already mentioned, it's worth spending more time to focus on the small regions where crackle reduction is actually needed. There are still sounds and noises that I do not remove from the recording, if they're characteristic to a given instrument. Such is the case, for example, with the attack of the brass instruments. The album we're talking about includes the track Chyba, że mnie pocałujesz ("Unless You Kiss Me"), which is based on the sound of bassoon. There are clearly audible sounds of metal flaps against wood there—deleting that element could result in the parties sounding very fake. One can see that there is something like creative, i.e. non-automatic noise reduction. On the example of those tapping bassoon flaps, I have to admit, I was only decreasing the volume of overly loud noises. Why? Because I believe this was the only obstacle for my auditory sense to focus on the emotional message conveyed the piece. But with a vinyl record, it's a completely different story—those mechanical crackles only add to its charm. Still, in those times, noise pollution was removed where possible. If not, these non-musical sounds were left there and as time passed, they merged with the crackles of a worn-out record. I believe that in the age of digital sound everything's "bare" and through that, extremely dependent on the player of choice. Hence everything that might pose as disturbance in the reception of a performance should be indisputably removed. What's your opinion on the problem of musical composition integrity, i.e. music-recording-medium format of choice? Previous editions had Mr. Niemen's "imprimatur". In literature, the final publication signed by the author is always considered to be the original. It seems to work differently in music. To what extent is the artist, say, Mr. Niemen, responsible for his work (music)? All the areas of musical composition integrity that you mentioned are equally important. Removing one of them might result in the work's unavailability for the large audience. In my opinion, this multi-dimensional approach guarantees safety. The owner of each element has the right to decide on certain aspects of the publication, and to disagree with the choices of others. For example, my dad never agreed to release the box set content in the mp3 format (which is constantly violated, by the way). Undoubtedly, the main reason was the reluctance towards the quality of mp3 sound. In this case, the right to decide should guarantee the protection of own work and artistic image. It's equivalent to setting boundaries and standards with which an artist and his/her work will identify. A good example of how an unauthorized person can be damaging to an artist's reputation is this anecdote about an album cover. It was a pirate cassette tape recording of one of my dad's earliest albums, with a parrot with Niemen's head pasted into the picture as a cover. If I saw something like that in a music store, I'd probably just assume it had something to do with cabaret. It turned out that such a flamboyant cover was to attract buyers. A whole range of such kitschy daubs can be found on YouTube, where it's unclear if someone is uploading home-made music videos to my dad's songs mockingly, or not. Unfortunately, culture and aesthetics cannot be taught if one did not develop a sophisticated taste in their adolescence, at the latest. I could still compare the original, in my opinion reference, analog releases to book publications, but I definitely wouldn't do that in case of digital versions. Please note that a particular digital sound that dad achieved was a reflection of a certain musical trend. Each age is characterized by certain technical inventions, musical trends, if one may say, which are created with the use of popular tools offered by the current (often very short-lasting) top brands. The "trend" can be easily determined by observing musical tendencies from a given period of time. I must also mention that there used to be, until recently, a trend in digital mastering to increase audio levels on CDs to make them louder than the rest, regardless of the musical style. Hence, it's difficult to compare the Od początku series with a literary form, where in the former, the medium is music, and in the latter it is word. Sound needs to be processed in order to reach the masses, whereas the author's "thought" is printed outside of technological development and emergent trends in graphic design. I think that the box sets could have been called the only proper releases of Czesław Niemen's work, if not for the previous, analog releases from the 1960s and 1970s. Niemen od początku is nothing more than remastering, an author's recreation of something that has already existed before. That's why the original release will always be a reference recording to me, accepted by my dad at some point, this way or another. The lack of attempt to remaster Dziwny jest ten świat in a way that would not be far from the original would be equivalent to throwing this cult recording away. As I've already mentioned, the biggest problem is the fact that there's still no digital release that would sound close to what's recorded on the master tape. I daresay that dad did not present us with the shape of a sound that we should stick to, but created a completely new one—an alternative quality to that of the original. I think that the binding "sound", rather than "release" (since it's on vinyl), should be what was recorded on the master tape. Besides, knowing my father, sooner or later he'd make more masters, being constantly unsatisfied with what he managed to obtain. With the new tools available that'd finally help him achieve his artistic vision, he'd probably never stop remastering his old releases. The question is, would he make the same assumptions as we did? I think that my dad's approach to mastering his albums was typical for an artist, but ours is limited to sticking to the original concept. Let me just finish my question, then—to what extent is the author responsible for his own work (music)? I believe that it all depends on what kind of an artist we're dealing with. My dad was often an author of musical compositions, which he performed both as the vocalist, and instrumentalist. From what he was telling me, he was frequently a music producer, too. Due to such a wide array of responsibilities, he always wanted to control everything. He always had a specific vision of what he wanted to obtain, which cannot be said about every artist-performer. I think that it's the artist who sets the boundaries of responsibility for his/her work, depending on involvement and self-awareness. What is the place of the mastering and remastering processes in the final shape of a music piece? First of all, I'd use the word "remastering" only (which actually covers everything that should be done during the process of mastering). Thanks to remastering, we can simply listen to what was released a long time ago and now can be made available on modern music media. To put it simple, remastering allows us to listen to what was recorded a long time ago. But as for the question about the role of mastering in the final presentation, that depends on other decisive factors. In this example, we can see how varied can be one's approach to remastering, comparing my dad's opinion from over 10 years ago, and ours. Did you have other releases in mind to refer to, while preparing this remastering? I've been collecting CD albums for years now. Very often I already knew them from my dad's vinyl records. I've been doing even more of that recently, always wondering about current musical trends and the direction they are taking. It turns out they don't always go in the best direction. That was the case with the last re-release of Dark Side of the Moon, which, in my opinion, sounds much worse than the previous one. I'll also mention Jimi Hendrix album Axis: Bold as Love from 1968. I have two editions, one from the early 1990s, one from 2010. In reality, these two differ only in volume, the latter being louder, in accordance with today's trends. The first remastering was done by Joe Gastwirth with Dave Mitson's assistance. The 2010 one was done by Eddie Kramer himself, who had recorded the musicians and produced the album. George Marino is mentioned right next to Kramer. And yet it seems worse.

Sound above all else, volume I ANALOG EDITIONS NIEMEN & Akwarele, NIEMEN & Akwarele. Polskie Nagrania "Muza" N 0497, SP LP. 7" "four", year of release: 1967

The predecessor of Dziwny jest ten świat, the "four" titled NIEMEN & Akwarele, is an inseparable part of this release. It contains the title track, as well as three other tracks that had been added to all of the digital versions that have been published so far (except for the newest one). The material has been remastered by the duet responsible for the "2014 Re-release", but it hasn't been included in the newest digital edition or released with the LP, which is a shame. It's worth remembering that Niemen had already once attached an additional single to one of his LPs, when he was releasing the album Idee Fixe. I believe it would be absolutely appropriate for NIEMEN & Akwarele to appear alongside the newest release.

Sound Singles have never been a very good sound medium, despite their higher rotation speed. Niemen and Akwarele's single is no exception to the rule. Its sound shows a lack of lower tones and flattened dynamics. On the other hand, the tonal balance has been very well preserved, and the top range, including the cymbals, is clear and resolving. It's hard to say anything about soundstage depth, because everything is shown quite flat. But taking all of that into account, what I truly found to be missing was the midrange saturation. But that's how music was recorded back then and there's no escaping it, I'm afraid.

Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza" XL 0411/SXL 0411, LP. "Blue label", year of release: 1967

There are some major problems with the first edition of Niemen's album. There's no clarity about its original cover art—the debate centers on the logo of Polskie Nagrania "Muza". In 1967, an edition with a thickly-varnished cover was published, while the logo had a "cockerel" instead of a "banana" and the words 'Polskie Nagrania' were in italics. The "banana" was on the back cover. The disc was being pressed for several years, but as early as 1968 there was a version with a changed logo and a "Golden Record" sticker on it, and some of them even had the sticker of "1st Place At the Youth Record of the Year Ceremony 1967" which I've mentioned before. The new logo was a "banana" which contained information about two different versions of the album being available—a mono version labelled XL 0411 and a stereo one labelled SXL 0411. I haven't come across a stereo version, though. All the center labels on vinyl versions I've seen indicate a mono record.

Sound Niemen's LP debut keeps the same tonal balance with a slightly raised accent, as has been previously showed on the "four". But there is some nice depth here and the bass, previously very modest, has much better articulation and definition. The cymbals are just appropriately sonorous and very nicely set within the big picture. Recessed Niemen's vocals are obviously a problem, as is not-entirely-satisfactory dynamics. You can also hear sibilance in Niemen's vocals—it was audible on all the turntables and cartridges I used, even the warmest ones like the Miyajima Labs Kansui. It's not the same as overemphasized hissing consonants on digital recordings that make them unplayable. In analog sound, sibilance makes it feel fresh and "open". It is, however, a step away from neutrality. Generally speaking, the sound is rather medium quality, but it does occasionally rise up to higher levels, e.g. in the intros or with individual instruments.

Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza" XL 0411/SXL 0411, LP. "Blue label", year of release: 1968

This is the 1968 edition, which you can see immediately by the "Golden Record" sticker added in 1968, as well as the fact that the original logo has been masked behind some kind of black, matted "circle", as if it were printed onto an already-printed cover of the 1967 version. Despite these differences it's generally accepted that both of these editions are synonymous—they have identical Matrix Code.

Sound The particular 1968 copy that I bought sounds notably different from the 1967 one. The differences can be heard in a few important aspects of sound. Most importantly, we get a more muffled sound with recessed treble. There is no sibilance, "jumping out" from time to time like it did previously, because there really isn't that much treble to begin with. The bass is also stronger, and the organs are better saturated. But everything sounds more hollow here, and Niemen's vocals are even more recessed, blending into the mix even more. The drums, on the other hand, has a more realistic effect of a small room's reverb on it—previously it wasn't that obvious. There are similar differences between various copies of the same release—while wearing out, the matrix first loses the treble, and then micro-information. But it's something more here, as if they had used a copy of the first version's master tape. The only fact countering my suspicions could be the better quality of some of the details. So I'm not 100% sure about it, but I'd still say that it's a slightly different edition and, in my opinion, worse than the 1st one.

Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza" XL 0411/SXL 0411, LP. "Red label", year of release: ?

One of my friends noticed that after the release of the album people said that while there were versions of it, one with a red center label and the other with a blue one, it was actually the exact same release. Their identical Matrix Code would confirm that, too. But this edition's cover art is different, which is why I treat it separately. The "banana" type logo is on the front, but it's blue, with a single catalogue number – XL 0411. Clearly, the stereo version was forgotten. The center label is red, instead of blue, but aside from the color differences the two versions are the same.

Sound I had assumed that the "red label" is identical with the previous edition, but that's not actually true. The sound is saturated, full, and has a large volume. It's a serious step forward in comparison to the 1968 version, and even—although on a smaller scale—to the 1st edition. The bass is stronger and deeper here. Although the copy that I have isn't as well-preserved as both of the previous ones I reviewed, I preferred listening to this one. Niemen's vocals were finally closer and they were large. The cymbals were resolving, like on the 1st edition, and the intros with solo instruments were powerful, feisty, and sounded really clean. Dense links to higher harmonics, which always add a feeling of warmth, were present and complemented other positive aspects I already mentioned. To me, this is the best edition amongst the "first three", i.e. the '67-'68 editions, because it's dynamic, selective and coherent.

Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza" XL 0411/SXL 0411, LP. "Banana label", year of release: ?

This edition has a clearly worse quality of cover art, but it returns to the original logo from 1967. On the back cover there's also the new logo of Polskie Nagrania "Muza". This record also has a different catalogue number—SX 0411 and it's the first re-release of this album after some years. Unfortunately, I don't know the year of its release. The most important change is the disc's center label—it's a "banana" color and it looks completely different than the "blue" and "red" labels. What truly surprised me is the presence of a mark claiming this album is stereo—that's its first center label appearance on Dziwny….

Sound I have a feeling it's the first time that Niemen's album was released the way it had been originally recorded, i.e. with a mono sound and stereo reverb. It might be quite interesting if it wasn't for the fact that the sound is bad. A muffled treble, a shallow and boomy bass, and most of all poor tone correction with a cut out upper midrange. There is no sibilance thanks to that, but there's no life in it either. The dynamics is flattened. Although, as it seems, the original master tape was used here, since the previous ones were mono (meaning they were copies), the whole thing was completely screwed up. A flat, boomy and dry sound, as if heard from a well. And it could've been so beautiful—there is good treble clarity (when you listen closely), clean reverb and large volume that makes for a nice presentation. Despite that, I don't recommend it!

Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza" SX 2547, LP. "Z archiwum polskiego beatu. Reedycje vol. 22" ("From the archives of Polish beat. Re-releases, vol.22"), year of release: 1988

This edition is regarded to be the worst. It definitely has the worst, skewed covert art of very poor quality. Nothing adds up here, not even the font color. The back side was also changed. The person responsible for the design was Ms. E. Pomorska. The album was released in 1988 and carries the SX 2547 label. The center label is "banana-colored" and aside from the added information "Z archiwum polskiego beatu" it's identical with the previous re-release. The "stereophonic" logo remains, too.

Sound Although the edition with the "banana" center label was weak, this one is even worse. It repeats all of its predecessor's mistakes, adding to the picture a poor resolution and even more muffled sound, as if a copy of that tape had been used. Let's add my copy has a definitely off-center hole, and we'll be in the clear. The sound is just as bad as the cover art. It's some abomination that should just be forgotten.

Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza"/Polskie Nagrania XL 0411/2007, LP. "Czarne perły vol. 2" ("Black pearls vol.2), year of release: 2007

This edition has a high quality cover art that is a return to the 1967 edition, including the logo and the disc's center label. I know that it was prepared by Ms. Iwona Thierry, who worked as a sound engineer and producer on many releases from Polskie Nagrania. It's said to have been prepared from analog tapes. I doubt that, though—it comes from 2007 and carries the Nota Aenigma logo, printed on a special cardboard "obi". And that means that the material was personally approved by Niemen. That means it was remastered by him in a digital domain. What's more – the pressing plant that was used this edition mainly presses discs from digital sources. It's also used by the Polish company GAD Records, which released a CD and vinyl records with music by Komeda, SBB, as well as the soundtrack from the Sonda TV show. The album was prepared as part of the "Czarne perły" series and carries the number "2". The first disc in this series was Komeda's album Astigmatic. The disc has a different Matrix Code than its predecessors and also contains information on the pressing plant: it's GZ Media (previous address www.gzvinyl.com). The plant is located in Loděnice in the Czech Republic.

Sound I spent most of the time listening to this version, flipping from one side to the other, coming back to previous editions, countering it with the digital versions. There are a lot of contrasts here. It has a lot of positive sides to it—it's a record with a truly low level of travel noise and little crackling. The sound is very catching, with emphasize lower midrange and part of treble. Hence, we have a return to the stronger sibilance from the first edition. Everything sounds selective and clear, as if the sound had been "cleansed". I'd say that this reminds me of Digiton's first digital version, if it wasn't stronger. It also has a better, lower and more coherent bass. Niemen's vocals are in the foreground and have a deep sound, which was missing on most of the previous editions. But there are also some faults that just can't be ignored. The resolution isn't as good as in the first three versions. The sound seems a little cleaner, more selective and better-defined, but only when "viewed from a distance". On the inside, it's poorer and more homogenous than, say, the "red" edition. If I was meant to rate it, it would get third place, right after the 1967 edition (2nd place) and the wonderful "red label". It's a surprising conclusion, even to me.

Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza"/Polskie Nagrania XL 0411, 180 g LP "Reedycja 2014" ("2014 Re-edition), year of release: 2014

The idea behind the newest pressing of Niemen's vinyl was to prepare an edition as close to the original as possible. The printing quality of the cover art is better than in 1967; there is no color shift and the lettering is much clearer. The photo of the band Akwarele on the back cover is also much better quality, and the cover itself right proportions. A lot of effort has been put in for nearly all of the ingredients of the first edition to remain on their rightful place. Although there are differences. On the first page, inside the Polskie Nagrania "Muza" logo, the fonts used for the "XL 0411" mark are different than the ones used in original releases from this label—their style has been taken from the "banana" logo on the back cover. The font of the little note on the cover's backside and the font of the track list and description has also been changed, which makes the text look more spacious. The price of the album has also vanished, and has been replaced by a bar code and information about the current publisher. The cover isn't lacquered with such thick paint as the original. The center label of the disc looks nearly identical, though. Despite all these changes it's the best re-release of this album. The disc is stored in a thick PVC sleeve – all the re-releases of Polskie Nagrania from this year and a year ago have been like this. Hey's album Do szlachty… has been released in the exact same way, meaning they're pressed by the same plant.

Sound While listening to the newest remaster of Dziwny… I referred back to the original from time to time. You can say it up front from the very start that the remaster shifts the tonal balance towards the midrange, emphasizing the density of the vocals. At the same time, it also strongly reduces the amount of treble. Yes, the textures on the new remaster seem internally thicker and richer, but also muffled. The dynamics seem to have been calmed down, too. I didn't know what to think about that until I took a look at both of the discs lying in front of me, side by side—the newer version has been squeezed onto a much smaller area than the original, automatically reducing the dynamics. I also think that the D/A converters used at the pressing plant had a problem with the top end. Although the sound seems dense and full, you can hear delicate "sizzle" on treble, unrelated to what's happening below. Ms. Thierry's version was very catchy, but it also remained in the spirit of the original in the sense that the tonal balance, except for the stronger bass, was similar to it. Ms. Atalay and Mr. Gawłowski's remaster is different and shows the material from a different side. It emphasizes the vocal's harmonies by withdrawing the treble and introducing some order in the relationship between the vocals and other instruments. The elements that stand "behind" the vocals have also been cleaned up, which makes the reverb clearer and stronger, so it actually makes sense now. I still think it's not an entirely successful edition. During its preparation several decisions have been made that may not have been the best ones, and the pressing added some of its own errors. Cutting the disc in this particular way, leaving a lot of unused space between the grooves and the center label instead of using it to space the grooves out as much as possible, is a big mistake. Cutting the disc from the CD version master (16/44.1), instead using a high-resolution master (24/192 would be best) was an equally serious mistake. Together with all the other errors they combine into something that can't really be regarded as a successful product. There were good aspirations and potential, but they haven't been used properly. And the 2014 digital re-release of Dziwny jest ten świat, which I will talk about shortly, is perfect, really fantastic. Hence, it doesn't seem to me that the problem is with the material itself, but rather with the method of producing the vinyl version. A shame, a real shame!

Sound above all else, Volume II DIGITAL EDITIONS

Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza"/Digiton DIG 107, CD. Year of release: 1991

At the beginning of the 1990s there were no CD pressing plants in Poland. The current market leader, Takt, used to manufacture cassette tapes back then, and the CDs from Polish as well as foreign artists (licensed by Polskie Nagrania "Muza", though) were pressed abroad. And it is there, in the Berlin-based company CDT BERLIN that the first digital version of Dziwny jest ten świat… was pressed. The album's first digital edition set the course for subsequent releases for years to come—in addition to the tracks from the original album, three other tracks were added. They had been recorded during the original session, but released separately on the "four" disc. The cover repeats the vinyl edition, without the logo of Polskie Nagrania "Muza". The photo is strongly brightened, looking overexposed and not really resembling the original. The layout of elements on the back side is similar to the vinyl, i.e. on the left side there's a photo of the band Akwarele. The typography describing the artists ("Niemen & Akwarele") has been preserved. The blue logo of Polskie Nagrania "Muza" has been added here, though, but a later version thereof than the one present on the original release—here we've got a music note overlaid on a black record. There's not even a mention of the text written by Niemen. That is found inside the ultra-thin booklet. The case is classic plastic, a.k.a. the jewel case or box. The disc has an ADD SPARS code (Society of Professional Audio Recording Services), which means a digital mastering. There's no mention of who the author of it is, but it's quite understandable that it's Niemen who tried to control all of the versions of his albums' releases. What's interesting, the disc also contains information that it's a stereo version.

Sound The sound of Digiton's CD is correct, and surprisingly sensible. The most important element is obviously Niemen's voice, and the instruments are set up behind him. Sometimes they are close, as on Wspomnienie, and on Dziwny jest ten świat… they're quite far up. The sound is rather light and not particularly saturated. But it's also clean, i.e. rid of any inner quivering. The treble isn't overly emphasized, although you can hear some louder sibilance in Niemen's vocals from time to time. But it's not the norm, and it only happens sporadically. The soundstage layering is also quite decent, with legible choirs by the Alibabki in the back. The drums are flat in terms of timbre and dynamics, but that's the nature of the original version. The musical events are clear and selective. I rate this edition as quite good, especially for something produced in 1991, when the art of analog-to-digital conversion was still in its infancy. Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza"/Digiton | Nota Aenigma DIG nae 101, Gold-CD. "Niemen retrospekcja" ("The Niemen retrospection"), year of release: 1995

This is the first release of Dziwny jest ten świat that features some of Czesław Niemen's graphic works—collages and photomontages—which also appeared later until they were all published in a box set. The album was released by the same company as the first one, i.e. Digiton, but in cooperation with Niemen's company, Nota Aenigma. The disc contains the information about it being a digital remaster. Importantly, it was pressed on golden by the Czech company GZ Media. The cover is identical as that of the first edition, except for the photo being slightly darkened, which did it good. The back has been improved, however, and now includes a list of performing artists and information about the recording. The disc, as well as the back of the cover, has the Nota Aenigma logo on it. It's missing the logo of the Polskie Nagrania "Muza"—but it'll be back with the release of "Niemen od początku vol. II".

Sound Niemen begins his search for the "right" sound with this album. In the meantime, it's quite a sharp turn away from what was originally released on vinyl. It seems that we're dealing with the exact same transfer as on the first CD version of Dziwny jest ten świat…, because the sound lacks clarity and selectiveness and is slightly muffled. The layering is also rather weak (in comparison with the analog original). However, being able to put his hands on digital files, Niemen made some fundamental changes when it comes to "stereophony". He moved the drum cymbals to the left channel and put a reverb effect on everything. What's more, he used some sort of stereo enhancement effect, which is nothing more than a manipulation of the signal phase. The vocals still have a pretty good consistency and most of the events happen on-axis. The real catastrophe is coming later… Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza"/Polskie Nagrania PNCD 353, Gold-CD. "Niemen od początku vol. II" ("Niemen from the start, vol. II", year of release: 1996

This is the second version pressed on gold instead of aluminum. Within the circles of people who take audio seriously, not only audiophiles but also music producers and publishers, it's been a well-known truth that gold CDs give you a different sound. It's partially about the way the CD player laser reads it and, what follows, a different error correction. We've written about this many times in the past, and the differences between aluminum and gold CD editions of the same albums are big and audible even to a casual listener. We've run many "blind tests" and the results always point to one conclusion (see HERE). The cost of a gold disc is only 3 cents higher from an aluminum one… Jarek Waszczyszyn has written about this while he prepared the gold edition of Jarek Śmietana's album (see HERE). In the case of Dziwny jest ten świat it makes particular sense, since it was a Golden Record, after all. This edition was created as part of a series of remasters, made by Niemen himself in his home studio, called Niemen od początku, and came with the number 2. He used 20-bit A/D converters for the transfer from the analog tape, clearly the same ones as those used on the 1995 version. I suspect that the initial material used for further processing was the same. The case is a transparent jewel box, with Niemen's graphic and the series name visible through the plastic. The cover is exactly the same as on Digiton's release, but it's been darkened—it makes a better impression now. The small booklet contains several Niemen's photos, some of which are collages. You'll also find a photo of the original Golden Record within. There's also a short author's note by Niemen from the year 1996. The back side, in addition to the track list and pictures of the band, also contains a list of performers as well as information about the people responsible for the recording and graphic art design. The disc again has a little note on it which says it's a stereo recording.

Sound It's a re-release full of paradoxes. Known for its "well-like" reverb it starts with a complete, artistic vision of the material that Niemen had in the middle of the 1990s, and the sort he was able to bring to life in his home studio with a certain toolset. Even due to this alone it deserves respect and is worth having as a document. The dominant element is the added stereo reverb, an emphasized pseudo-stereo effect. It gives you the impression of a large space. The mono sound is gone, in the sense that it now takes up the space between your speakers, and not only on-axis in front of the listener. You can tell that the artist cared about adding soundstage depth and detaching the instruments from its center. It resulted in an effect that wasn't very well-received by music lovers. Personally, I don't like it very much, either. Niemen's vocals, on the original edition firmly anchored in the front and having a solid body, here sound washed-out and shell-like, hollow on the inside. The case is quite similar when it comes to the instruments, although in their case you can hear one more thing that Niemen attempted to improve—a change in their clarity. The artist emphasized the attack and selectiveness to make the whole thing sound more dynamic and resolving. But along with the brightening of sound and poorly defined bass, it also brought an impression of garishness and chaos. Although the intentions were different, I'm sure, the sound is much too forward, especially in louder moments, and even seems to be overdriven. The cymbals are clear, and you can finally hear what's going on there, while the bass drum and toms seem to have somewhat of their own sound. But much like Niemen's vocals they are "hollow" inside. Sharpening of the sound also has a negative impact on the timbre of the vocals—it's too bright and forward now. Although the album was pressed on gold, which should always result in more warmth and smoothness, none of that remained here. This, in my opinion, is the worst digital version of Dziwny jest ten świat…. It's certainly a historical document, but can it be used for listening—not really. Dziwny jest ten świat. Polish Records "Muza"/Polish Radio | Polish Records PRCD 332, CD. BOX SET "Niemen od początku vol. 2" ("Niemen from the start vol. 2"), year of release: 2002

This version is part of the first of two "box set editions" containing albums from the Niemen of początku series. Two box sets were necessary to cover all of the artist's works (excluding the albums Terra Deflorata released by Poljazz and the later Spod chmury kapelusza) (you can find more information about "box set" releases HERE). It's the first Niemen's CD release pressed on aluminum by Takt. Instead of a plastic case, we get a digibox with matte print and a picture that lacks the noble colors of the original, and is slightly bluer. The original typography was left, even though there's no logo of the Polskie Nagrania "Muza" present anymore. Also, since every box set came with a booklet, there is none included here. For the first time, there's no information about "stereophonic sound" on the record, but we get the ADD SPARS code. The back cover is a replication of the previous edition, with additional information that the author of the covert art design is Czesław Niemen, and that he used a 24/96 digital reconstruction (in other words, using newer A/D converters than before) and finally, that the mastering was done in his NAE Studio. We also have information that Gina Komasa was responsible for consultations, and Monika Mandau and Jan Popis for the editing. The album was released by Polskie Radio, in cooperation with Polskie Nagrania. The latter's logo is still at the back, and it's colored.

Sound I think that this version has to be treated as a correction of the 1996 "gold" edition. It's another one of Niemen's visions of what his works should sound like, and another example of how it was shaped by the time period in which it was created. Here we're dealing with a victim of the "loudness war", or a tendency that Ms. Atalay has already mentioned—to use extreme dynamic range compression in order to increase the average signal level as much as possible (more information HERE). It results in a sound that seems louder and more dynamic, hence, better. In reality, it's flat and artificial. The sound of this version of Dziwny… is specific. On the one hand, the compression used really does amount to high loudness. Such recordings sound better on TV or radio. Niemen also changed tone control on these recordings, adding more mid-bass and less treble. Both of these things, i.e. stronger compression and tone modification, translate to quite large phantom images, with a large volume, "present" between the speakers and somewhat "tangible". It's undoubtedly a good direction, because the material finally has some solid weight and isn't so "thin". But the "pseudo-stereo" effect known to us from the previous edition is used here, too. It results in much poorer treble, even worse than on the previous release. There, the better selectiveness achieved by sharpening and emphasizing the attack resulted in a clearer image of the cymbals. Here, the changed tone left very little of that effect, apart from an overwhelming sensation of blur, as if the cymbals and brass instruments went through a "diffuser". Generally speaking, this is not a bad version of the album, and all in all, it's much better than the two previous ones—it doesn't, however, match up to the first, German-pressed edition. Dziwny jest ten świat. Polskie Nagrania "Muza"/Polskie Nagrania PNCD 1570, CD. "Remaster 2014", year of release: 2014

This edition of Dziwny jest ten świat has the best cover art design. The cardboard box has three segments, and the booklet is stuck onto the middle one. I think it might be better to put it into a cut-out. On the left side there is something that looks like a mini LP concept know, from Japanese editions. Not entirely, because it's not a square as in the LPs' case, but it's close. The cover photo and typography are definitely the best-looking out of all the editions so far. The original logo of the Polskie Nagrania "Muza" was also kept, although without the label's name. Funnily, it's not the same logo that was on the first 1967 release of the album, but the one from the later 1968 version of it. The "banana" on the 2014 remaster was initially on the LP back cover, which here is an identical replica of the original back cover. The only thing that's gone is the price (65 zł) and a notice about the label name has been added. The remainder is the same. The disc slides into the "cover" as you would slide a record into an LP cover. The disc comes wrapped in a paper sleeve to prevent scratching it. I would rather exchange that for a Japanese cotton sleeve, available on Ebay, for example. The record has been released in cooperation with the Czesław Niemen Foundation.