|

You are reading the older HTML site Positive Feedback ISSUE 9 october/november 2003

Dog

Yummies - Autumn 2003 Wagging My Tail Reflections From The Cornfield: Making Bricks Without Straw "Peter

is poor," said noble Paul,

"You’re

a bad man, a very bad man."

Overture Motoring up to San Francisco from the south, through thousands upon thousands of acres of grape vineyards and vast expanses of rolling hills so barren of green grass they looked like hairless cats in the amber light of dusk, I found myself pondering the fertility of the economic soil for the rollout of yet another Primedia (Home Theater, Stereophile Guide to Home Theater, Stereophile, and Audio Video Interiors)-sponsored showcase of high end, two-channel audio and home theater products. Much as the arid valleys leading into San Francisco have proved fecund to none in terms of agricultural productivity—when provided with a steady supply of water—for those high end audio designers who chose to incur the cost of exhibiting at Home Entertainment 2003, it seemed as though, at first glance, they were inspired anew to blossom and bloom by the steady streams of audio enthusiasts who flocked to the Westin Saint Francis to take their measure of the audio/video industry’s creative edge. Nevertheless, I’d been haunted by a number of nagging questions throughout the summer months as I sat down to gather my thoughts and toss about some best-sound-of-show bouquets in the general direction of two-channel audio’s leading lights (Editor: Chip gets the last word on the show in his Best of Breed roundup over on the 6moons.com website). For all the wonderful sound systems I heard and all the lovely people I met in the city by the bay, I felt as though simply dashing off another show report would be kind of an empty gesture without reflecting at length on the tough times we’ve all been going through, as manufacturers and retailers alike endured a nuclear summer of consumer ennui. More troublingly, as summer turned to fall and the literal wildfires in Southern California echoed the economic conflagration overtaking our industry, it was unsettling to discover that we could no longer look towards two-channel bellwether Stereophile for succor, leadership, and support. In fact, over the past few months, every single time I sat down to write this article—with an eye towards cultivating some sort of dialog as to how our industry and its leading publication could nurture each other’s growth and prosperity—Stereophile and Primedia countered with a series of befuddling moves that were widely interpreted as antithetical to the interests of both two-channel manufacturers and brick and mortar retailers. Talk about sending out mixed signals to the very people who financially underwrite your enterprise, and who in turn depend on you for in-depth, articulate coverage. I mean, we’re all in this together. This Thing Of Ours How exactly is one to interpret the writing in Primedia’s entrails? Before we book passage for that Stygian descent, let us backtrack a bit. First of all, how cutting was that creative edge at the San Francisco show? Or, as one local audiophile phrased the question after buttonholing me at a Manhattan bistro, "Were there any developments so innovative, so far-reaching and revolutionary that I should toss out everything I own and prepare to adopt a new system?" Sigh. Such is the message your average Joe gleans from all our highfalutin’ technology—that somehow this is a capricious, elitist process that excludes those not prepared to pony up for every new audiophile wrinkle, no matter how ephemeral. I thought back to my experiences of early June, referenced a variety of new projection systems, the rollout of multi-platform, high-resolution digital machines, and sundry variations on a multi-channel theme. I pondered the new generations of downloadable media and wondered aloud as to how much impact the high end audio industry would have on these brave new worlds of digital convergence and distribution. I went on and on about all of the great-sounding rooms I’d experienced, but when, in the face of this fusillade of information, my friend’s expression registered a decisive NO SALE, I summed up my sense of the show and my gut feelings as to where it was all heading with an elegant two-step: "… evolutionary, not revolutionary—a series of musical enhancements and refinements on our beloved two-channel/proscenium arch perspective. Soul-stirring, deeply satisfying, but hardly revolutionary." Which sort of encapsulates the current state of the market. Is two-channel finished? Hardly, but it is clearly diminished. The party ain’t over, but there’s no more open bar. Everyone has to pay for their drinks, up front and in cash, because the baby boom is over. The post-Beatles cultural explosion that ignited four decades of unparalleled growth in the music industry is over. The Asian market and Pacific Rim spending spree that fueled the furious high end audio expansionism of the 90s is played out. Manufacturers that postured as if they were the wind are now revealed to have been but a sail, unable to posture and front without a wave of fresh capital or a fresh breeze of new ideas to carry them forward.

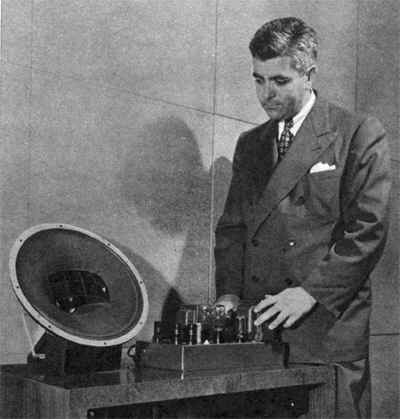

Avery Fisher, Saul Marantz, and David Hafler are all gone, but two-channel now finds itself going back to the future, and guess what—it’s 1959 again. Knock knock… anyone out there? Of course there is, but how do we reach them and get them excited again? That’s the challenge facing two-channel audio, unless we want to move the clock back to 1949. Do we paint too bleak a picture? Well, the post-9/11 malaise, the bread and circuses of George Bush’s foreign policy and the general economic downturn haven’t just impacted two-channel audio, but the music industry as a whole. And even if you factor out such catastrophic events, the mendacity of man and sundry acts of God, some sort of big adjustment was coming once all of that baby boom money ran out. It was simply raining money in the 1960s, after the Beatles hit and created a worldwide market for all things music. Not surprisingly, musical instrument companies grew fat and complacent as their comfortable little niche industries were transformed overnight by the seemingly insatiable international demand. Soon enough, these little boutique enterprises were swallowed up by huge corporate giants, who floated a mountain of debt to finance their acquisitions with little interest or understanding as to how quality or tradition might translate into a more bountiful bottom line. Companies came and went, got bigger and more ambitious, then came back down to earth as the last virgin markets were saturated with instruments, baby boomer money dried up, and they were forced to come to terms with reality. As individuals and as an industry, they learned once again how to navigate in a niche marketplace—how they needed to structure their industry to remain viable, to develop new generations of consumers, and to prosper on a less grandiose level in a different kind of economic climate. Then of course there are the ongoing hot flashes of a commercial recording industry in the advanced stages of cultural menopause—slow to embrace the Internet, hostile to a new generation of downloaders, stubbornly plodding along doing business based on the gas-guzzling paradigms of hits, airplay, and massive rollouts of schlock product through a monopolistic distribution system that arose in the post-Beatles epoch. Having essentially destroyed retailers’ ability to maintain a competitive posture with escalating list prices and ever-shrinking margins, they woke up one morning to discover that there was no one ready, willing, or able to help them break the one or two "new acts" a year that traditionally yield multi-platinum sales and expense account profits sufficient to keep the wheels of corporate commerce a-spinning. Is it any wonder that they are reeling from tumbling sales and consumer ennui? They killed the golden goose. And what of two-channel’s golden goose? Well, it is the victim of a cumulative roasting. Solidly made and affordable (if relatively dreary sounding) mid-fi gear has saturated the marketplace, and our industry has not made a compelling case to the public for larger, long term investments in true high-resolution gear. If you watch those brilliant Bose infomercials, you can see how cleverly they manipulate the public’s misperception of high end audio as an ungainly, unconscionably expensive, over-complicated mess by offering a no muss, no fuss, plug-and-play alternative in its stead. In addition to the drying up of Asian markets and the stagnant nature of the American economy, the music market has become very fragmented and sluggish. Plummeting interest in the desultory product of the recording industry has certainly impacted the high end. The demographics of aging baby boomers indicate that they are not inspired enough by new music to seek out better playback gear, have already updated their LP collections with CDs, and are content to sit tight with their old systems. Or, to paraphrase what my friend asked me at the beginning of this piece: "Is there something out there so exciting that I should simply toss away all of my old stuff?" Major parts of the high end audio industry have hedged their future on the rollout of new high-resolution digital technologies, yet have been loathe to accept the popularity of downloadable media and "lower resolution" formats. But the quick acceptance of iPods and the iTunes-type services point to a cyberspace version of the old fashioned, pre-LP, record-shop-listening-booth style of shopping. High end audio, like the record industry, seems to view this development more as a threat than as an opportunity. In truth, for the type of music that is so popular at the moment, computers, portable media, and car audio are often the delivery system of choice. Then of course, there’s the manner in which the high-end audio industry has ceded its marketplace to the multi-channel/home theater/custom installation types. A tidal wave of mid-fi gear, in the form of inexpensive DVD players, set the stage for this marketing stampede worldwide. Clearly, at this time in our history, movies and visual media have far more appeal and cachet as big ticket items than pure audio, but again, how well has the consumer electronics industry sold people on the joys of good two-channel audio? Not very well, and hey, let’s face it, there’s a lot of sales out there in big screen TVs and in-wall speaker systems, where you don’t even know how the motherfucker is going to sound until it’s bolted into your mantelpiece, and by then it’s too late. As for audio growth through the onset of surround-sound music formats—even with the rollout of some excellent multi-platform players that can handle two-channel and surround applications with aplomb—at this point in time, the hardware is still light years ahead of the software. This is the subject for a dedicated, full-length feature of its own, but after attending the Meridian DVD-A surround sound demo at Home Entertainment 2003 in San Francisco, let us just allow that, to these ears, it was a joke. Not the Meridian gear itself—no, that was first rate—but the software. There were incremental enhancements in ambience on a church organ piece, and effective deployment of human voices on a choral ensemble piece, even a nice semi-circle effect as if sitting around a campfire on a 70s Emmylou Harris bluegrass remix. But a recent Fleetwood Mac recording sounded utterly horrific in 5.1, yet quite good in stereo. (Blame Mick Fleetwood was the consensus.) The mix of a Clapton/B.B. King recording was much more musically executed, but in its diagonal array of intersecting guitars and such seemed gimmicky and unnatural. Clearly, this industry still has something meaningful to share with devout music lovers, and there is still a very persuasive case to be made for the realism, immediacy, and emotional involvement of high-resolution, two-channel audio, yet the message is not getting across the way it might if we are to attract a new generation of consumers. Something much more jaded and off-putting is coming across instead. A key element in the cumulative roasting of two-channel’s golden goose is that our leading clerics have grown accustomed to a chorus of amens from the same congregation, over and over and over again. As a result, we now reap what has been sown in the form of generation upon generation of quasi-audiophile "critics"—jaded little reviewers who care less about music and more about some mystical form of ego pride in which they assert their ability to hear nuances of perfection that mere mortals such as you and I don’t have the taste or refinement to perceive. These legions of Mini-Me’s dutifully parrot the language and jargon originally expounded by such tribal elders as Harry Pearson and J. Gordon Holt to communicate nuances of resolution, then emulate and promulgate the received wisdom of other elitist wannabes in a gigantic circle jerk on Audio Asylum, Audiogon, and sundry chat rooms. (Never mind the covert cells of paid hacks lurking surreptitiously therein to mount campaigns of disinformation against certain manufacturers, while anointing false prophets for a fee.) I certainly don’t wish to denigrate the contributions of Harry or Gordon, nor to dismiss the earnest seekers after truth who turn to the aforementioned circle jerks for jewels of insight that might enable them to achieve system synergy and enjoy a deeper experience of music, but the manner in which the message has been passed down loses something in the translation, and is a colossal collective turnoff to nonbelievers and potential converts. Thus, in slogging through thousands upon thousands of obsessive postings, one gets less of a sense of joy through immersion in music than of the self-referential/self-serious side of our thing—watered down, secondhand versions of vintage Harry Pearson, wherein it seemed as though all of the battles for the soul of high end audio were being determined by heroic jousts in his living room.

The Primedia Directives, or, They’re Breaking Up that Gang Of Mine This is where two-channel audio finds itself today. And this is why I delayed writing a Home Entertainment 2003 Show Report (let alone this massive rant) until I would literally have the last word, right after Stereophile published their authoritative, in-depth coverage of the San Francisco Show in the eagerly awaited October 2003, Recommended Components Issue. Little did I know how underwhelming that would be, nor could I anticipate the cumulative impact of the astonishing series of decisions emanating from Primedia’s corporate hierarchy, and how counterproductive they would be both to the health of this industry and to the sustained prosperity of Stereophile itself.

Because for all the foot traffic, little if any of that glad hearing translates into sales, not that it ever did. We are not talking about "wall to wall qualified customers," as a recent Primedia press release sought to portray show attendees. Everyone in the industry knows that is nonsense. But then, that is part and parcel of a critical lack of awareness amongst Primedia’s corporate managers as to how much this industry depends on Stereophile’s support, and how much we may sink or swim together. No, the great thing about these shows, going back to when then-Stereophile publisher Larry Archibald was staging them, was that they were consumer-oriented events that supported a dialog between audiophiles, fledgling listeners, audio journalists, and audio designers. Unlike the winter CES in Las Vegas, where the focus is on a quantifiable level of commerce—allowing manufacturers and retailers, distributors and reps, to make a connection and do some serious business—the experience of the Stereophile Hi-Fi Shows was always about immersion in a sonic event, the celebration of our thing. A listening party. Which, by and large, it still is—a great hang, and a whole lot of fun, for listeners. But what short or long-term bounce do the exhibitors—who foot the entire bill—get from this feel-good event? For manufacturers, time is money. It’s one week out of fifty-two, a pricey exercise in good politics, smiley-face PR, and good vibes. Can you please play my CD? Manufacturers chalk it up to consumer education and a backhanded show of support for Stereophile, the most esteemed and influential of the remaining audio print media, whose outreach and authority is analogous to that of Mix in pro audio and Car & Driver amongst automotive enthusiasts. Stereophile: a name brand synonymous with the product, the industry, and its audience.

Seemingly oblivious to the implications of their cost-cutting frenzy, Primedia is allowing this important magazine to slowly circle the drain. Despite being forced to get by with ever-diminishing resources, Stereophile remains under constant pressure to maintain levels of advertising revenue commensurate with Primedia’s lofty expectations, even as Primedia’s corporate managers continue to cut back on the very editorial pages that signify the most tangible gesture of support extant to an audio industry in dire need of in-depth coverage. It’s not unlike Pharaoh asking the children of Israel to go forth and make bricks without straw. In a further irony, instead of employing revenue streams derived from the recent Home Entertainment Shows to buttress this valuable property—and by extension the very industry providing said revenue streams—Primedia continues to bleed the property dry. At the same time, in an inverse form of reasoning, the Incredible Shrinking Stereophile is being positioned as a stalking dog to justify the staging of future shows. Want further proof of Primedia’s lack of sensitivity to the needs of the high end audio industry? Even as their marketing machinery was trumpeting the budget-busting concept of bi-coastal consumer shows in both the spring and fall of 2004 (Home Entertainment East at Manhattan’s Hilton Hotel from May 20-23, and Home Entertainment West from November 4-7 at San Francisco’s St. Francis Westin), Primedia wouldn’t even allocate enough editorial pages in the October Recommended Components edition of Stereophile to provide editorial coverage of their own show!

Are we suggesting that Primedia shouldn’t look to make money from Stereophile or from sponsored events? Hey, get real—they’re not the United Way, and the basic formula of balancing editorial pages against ad pages and paid circulation still holds true. The issue isn’t whether Primedia has a right to make a profit or not. The problem is that they are not supporting the industry as much as they could be. Such a shortsighted lack of support is clearly having an impact on their bottom line, and on that of the industry that looks to them for support. No, the purpose of this article is to make Primedia conscious of the fact that there are opportunities aplenty for profits and growth in two-channel audio, but only if they are prepared to work closely with the industry. The problem is that Primedia is clearly out of touch with the two-channel industry, their marketplace, and their readership. The problem is that mounting a second Home Entertainment Show is a very bad business decision. The problem is that firing Group Publisher Jackie Augustine right after Home Entertainment 2003 in June sent a very dubious message to the industry. The problem is that firing Stereophile Publisher John Gourlay in the beginning of November sent a very bad message to the industry. The problem is that failing to even cover your own tradeshow in your own publication sends a very dubious message to the industry. The problem is that aligning Stereophile’s web site with Audiogon to form an on-line AV Marketplace sends a very bad message to the brick and mortar retailers who advertise in the magazine and support the Home Entertainment Shows. You might as well change the name of the magazine to StereoGone. The problem is that these questionable business decisions are tantamount to Primedia abandoning the two-channel audio industry even as it solicits increased revenue. The problem is that as a result of all this mischegas, Editor John Atkinson finds himself between a rock and very hard place, putting on a brave front as if he were comfortable with all of these decisions as the magazine begins to circle the drain. How did we arrive at this point?

Reflections From The Cornfield I came on board at Stereophile at the apex of its ascendancy as the bible of high end audio, and though I’ve since been wished into the cornfield, it distresses me to see the corporate culture in which the magazine presently operates threatening to cut off vital elements of its life support system and, by implication, a major source of life-giving water to high end audio vineyards already withering under the blistering heat of a protracted economic drought. Things seemed so much brighter back in the late 90s, when publisher Larry Archibald, already a fairly well-to-do-fellow, cashed in his chips, as Stereophile Inc., the corporation jointly owned by Larry and editor John Atkinson (though clearly Larry possessed the bigger joint) was sold to mega-media octopus Petersen Publishing. In hindsight, it’s clear that Brother Archibald turned over his share of the property at the very peak of its value. Thereafter, in short order, E-Map absorbed Petersen, and Primedia in turn swallowed up E-Map. With every additional layer of corporate bureaucracy came another level of debt financing, and additional pressures on every profit center within the corporation to max out revenues and help decrease the debt. Fall below a certain level, and they’ll pull the plug on you in a New York minute. Perhaps Larry took seriously the notion of his advisory role with the new owners, but I gather they didn’t put too much stock in it, and as I watched him wander the hallways of the 1998 Los Angeles Home Entertainment Show with new group publisher Jackie Augustine (recently consigned to a cornfield just adjacent to my own), introducing her around to writers and exhibitors while offering a personalized crash course in the nature of the audiophile lifestyle as both a business and a calling. I sensed a certain melancholy in his demeanor, and while wheel barrels full of dead presidents can mitigate truckloads of melancholy, Larry genuinely loved the gear, the exalted level of music reproduction, and the gamesmanship. Gazing into the eyes of our Dickensian paterfamilias, I thought I gleaned a glint of darkness, the dawning realization that he had not, in point of fact, trundled off his most beloved child to an upscale boarding school, but in all likelihood had delivered him unto a Bleak Street workhouse. Alas. Still, despite all the aforementioned gloom and doom, the magazine that emanated from the insights and perceptions of audio visionary J. Gordon Holt (third cornfield past the graveyard) remains a going concern, an influential publication that turns a profit. Stereophile carries on, reduced in scale if not in stature. Or as a humbled, repentant Ebenezer Scrooge might beseech the Ghost Of Audiophiles to Come, "Are these visions of the way things must be or how they might be?" So in a sense, Making Bricks Without Straw is a cautionary tale. In forcing the magazine to defend its very reason for existence as a specialty audio publication; in making editor John Atkinson churn out a complex monthly product with minimal resources and a skeletal staff (while shouldering responsibility for all equipment testing and measurements), in severely limiting the number of editorial pages available for an ever-diminishing degree of product and music coverage, and in turning more and more to these Home Entertainment Shows as a ready source of cash, Stereophile’s corporate managers not only risk choking off a sustainable supply of golden eggs, but of gassing the goose itself during this economic downturn. More’s the pity, because our industry would be a whole lot poorer for the magazine’s demise.

But speaking in the past tense from the perspective of the cornfield, it’s worth noting that John is a complex, enigmatic fellow and a rather challenging individual to work with. I contributed to his magazine for some seven years, and probably have less of a sense of him as a cat than I did when I first met him—only that his native shyness can’t disguise a very strong-willed, hardheaded individual with a formidable ego. Which is part and parcel of what has enabled him to maintain the focus and direction of Stereophile over the years, and to safeguard that vision in the face of corporate meddling. But he also has a tendency to run hot and cold on people, and so one day you might be among the elect and the next day you’re off the radar screen and busting kernels along with such distinguished cornfield alumni as J. Gordon Holt, Robert Harley, and Jonathan Scull. Huh, what happened? Well, you don’t necessarily know because it’s never directly communicated to you. And so it goes with creative people, and John is nothing if not creative, and nothing if not proud. I have to hope that pride won’t precede a fall. Clearly the strain of the gig and of maintaining the magazine’s approach is taking its toll—both John and the magazine seem to be getting smaller. Bit by bit, the pages drop away. Music features and record reviews, always a strong suit of the book under Richard Lehnert and Robert Baird, have shrunk to negligible levels, while the coverage of audiophile software has disappeared altogether. In order to maintain a comparable number of equipment reviews, the breadth and length of those reviews has been scaled back. There’s hardly any room at all for in-depth industry features and interviews concerning technical issues, engineers, and audio designers. Nevertheless, when one of John Atkinson’s audiophile recording projects is hot off the presses, you can bet your life there’ll be a full-length feature taking up page after page in Stereophile, exhaustively detailed and annotated down to the last microphone cable. And so, when I saw a cursory photo essay of the 2003 Home Entertainment Show rather than a detailed written analysis by all of the contributing editors, I had to wonder if John was hearing footsteps from Primedia corporate or if this was simply an emergency-room triage call for which he wasn’t given sufficient editorial pages to accommodate both Recommended Components and the Show Report, meaning that the Show Report ended up sleeping with the fishes. Not a very propitious decision, but maybe John had no choice. Still, when 6Moons’ Srajan Ebaen recently engaged Brother Atkinson in a chat room discussion touching—among other things—upon the egregious StereoGone Audio-Video Marketplace, Srajan told me that John made it perfectly clear to him that he was very much in charge and these were all his decisions. That being the case, do you have any idea how profoundly a Stereophile alliance with Audiogon undermines the very high end audio retailers and manufacturers your marketing people are trying to sign up as advertisers and exhibitors at two Home Entertainment Shows in 2004? Maybe you should take the time to ask, John. You might be surprised by the answers. Where Do We Grow From Hear?

Hopefully, Primedia’s recent rounds of cost cutting and consolidation will trigger a rededication to their entire Home Technology and Photographic Group. Replacing John Gourlay as the publisher of Stereophile (as well as Home Theater and Stereophile Guide to Home Theater) is Jay Rosenfield, who created Video magazine in the 1970s (according to the press release, after the title was sold to Hachette Filipacchi Magazines, he served as Video's publisher for three years, and subsequently served as publisher of Vail Beaver Creek and Rocky Mountain Golf magazines). Primedia has a major stake in Stereophile, and if they want to fatten up that golden goose enough to support not just one, but two Home Entertainment Shows, they need to give something back, to invest whatever time and resources they can to foster growth in the audio industry, not only to give it legs, but wings. We all sink or swim together. Without progressive marketing strategies to promote our industry and to create interest amongst disaffected consumers, manufacturers will more and more come to view this show as something that nurtures congenial relations with the magazine and benefits Primedia’s bottom line, while unable to quantify how it profits them. If you look at an issue of Stereophile from seven years ago and compare it with the most recent issues, it’s obvious how thorough a turnover there has been amongst advertisers, and how many of those companies are no longer in business, though for every company that gave up the ghost, it seems as though another two arise to take their place. This illustrates both how volatile the high-end audio industry is and how vulnerable many of these businesses—SMALL businesses—are to any and all short term setbacks. So it’s not just a matter of who has the best-sounding product or the best-sounding room, how cool the Richard Thompson concert was, nor how hot the chatter about single-malt-fueled meltdowns at show seminars. CES is a business show—with dealers and manufacturers talking turkey, cutting deals, making sales. If the Home Entertainment Expo is going to continue to be a people’s show—in which the average consumer gets to sample the advances and refinements in high end audio technology and theoretically gets to gauge how it might impact their buying decisions—the degree to which consumers and manufacturers are able to make a cost-effective connection with each other will determine the degree to which the corporate sponsors of Stereophile and future Home Entertainment Shows will be able have their cake and eat it too. Again, no one is faulting Primedia’s corporate mission to turn a profit, but they’re clearly out of touch with their market and confused as to the nature of the property they’ve acquired. That is to say, what constitutes Stereophile’s readership, and what are they yearning for? This is not a general-interest magazine but a specialty publication serving a lively niche in the socio-economic food chain, not all that different from publications covering motorcycles, fishing, gourmet cooking, etcetera. Sure, these are tough times, and outsiders cannot be expected to fathom all the ripple effects of an economic downturn on a complex, multi-tiered corporate entity such as Primedia, with the clear and present necessity of maximizing profit centers while keeping costs to a bare minimum. But the implications of downsizing Stereophile hasten the day when an otherwise vital publication might have to be put on life support well in advance of the inevitable upturn in the economy. It is incumbent on Primedia to work with the high end audio industry to create cost-effective incentives for more and more companies to exhibit. Why are exhibitors assessed a premium for sharing a room with other manufacturers, instead of being allowed to defray the costs? Why isn’t there more emphasis placed on organizing the event to generate sales? A recent press release, which characterized the Home Entertainment Show as "wall to wall qualified buyers," is patently absurd. And why, on top of the already formidable shipping, transport, and lodging costs out-of-towners must incur to mount an effective demo in expensive locations such as San Francisco and midtown Manhattan, are exhibitors expected to whistle a happy tune as they are left to fend for themselves in the face of featherbedding union types who exact a Soprano Family tariff for simply moving about sets of boxes on dollies? Horror stories amongst exhibitors abound, and with each fresh atrocity, the willingness of manufacturers to be involved in this cooperative enterprise diminishes significantly.

As a show of good faith, and of support for the high end audio industry that nurtures its golden goose, might it not profit this corporate enterprise’s long term revenue streams to show faith with its current and future advertisers by adding another 8, 16, 24, 32 more pages of pure editorial space in Stereophile so as to offer expanded coverage of audiophile recordings, and all of that sexy new hardware Primedia hopes to see on paid display in the halls of a pricey Manhattan hotel come next spring? And why not give high end’s flagship publication some fresh editorial staffers to help grease the wheels of commerce, so that more and more new products can be measured, evaluated, and published in each issue? Is that so much to ask? Apparently it is, because Primedia’s message is "Ask not what Stereophile can do for the audio industry—ask what you can do for Stereophile." To that end, despite cautionary feedback from the high-end audio industry, Stereophile and Primedia are forging full speed ahead with plans for two trade shows. Perhaps I have deluded myself into thinking that Primedia is still committed to two-channel audio and music, when all indicators are that the future emphasis will be on Home Theater. Let’s look at how Primedia is promoting the shows for clues as to their thinking. "According to all reports received, the Show was an incredible success," reads this chest-thumping press release from June 23 on the Stereophile website. "As calculated both in consumer traffic, which totaled 15,123 people, and the more than 1000 retailers and 483 members of the press from all corners of the globe. Show attendees had a chance to see, hear, and demo more than 250 brands from 200 exhibitors in more than 100 demo rooms—over $10 million worth of audio/video and home-theater equipment."

In other words, the exhibitors bear the total cost of staging this show. And how exactly does this benefit them? Let us ponder this rationale as offered by Irwin P. Kornfeld, the new vice president and group publisher of Primedia's Home Technology & Photography Group and executive director of the Home Entertainment Shows (which appeared September 22 on the Stereophile website): "Our shows in both New York City and San Francisco have been very well attended events. And, given that today's consumer wants to stay on top of the new technologies and components as they are introduced, we've got to reach the readers of our magazines, and our show attendees in these important markets, more frequently. These shows give manufacturers and local retailers the perfect opportunity to showcase their products in an informative setting and at an event that consumers have grown to trust. When it comes to getting the best advice, knowledge, and information, the Home Entertainment Shows keep qualified customers at the forefront and in the market." We’ve got to reach the readers of our magazines, and our show attendees… more frequently… keep qualified customers at the forefront and in the market. Well now, isn’t that the purpose of the magazine itself? And might not the most effective means of reaching readers and inspiring auditions and informed buying decisions be to give them the broadest, most detailed, informed coverage possible? How exactly do you grease the wheels whereby show attendees evolve into qualified customers? Let’s hear it from manufacturers and retailers, shall we? Can you come forward and quantify how all of that activity in San Francisco translated into sales? Did you notice a bump in business—as in orders—coming out of the Bay Area immediately following the show? Four months later? Compared to the year before without a show?

This means that most of the manufacturers I speak to are debating whether or not it even makes sense to attend the 2004 Home Entertainment in New York, let alone to attend two! Meanwhile, some advertisers are already grousing about whether or not it makes sense to commit to a budget in Stereophile and its sister publications, let alone two expensive consumer shows, when there isn’t enough room in these publications to cover their products in a timely manner. They wonder why they should support Stereophile and its sister publications when these magazine are unable to fulfill their mandate to provide in-depth, informed, critical coverage for their readers, let alone all of those "qualified customers." Why support Stereophile or Stereophile Guide to Home Theater when Primedia won’t? For Primedia to utilize Stereophile and its sister publications as a means of promoting not one but two annual consumer shows is like asking the mighty Seabiscuit to pull a milk wagon. Hell, even the folks who mount CES in Vegas long ago gave up the notion of trying to squeeze two shows a year out of their exhibitors. Primedia has yeoman work to do just to convince people of their commitment to Stereophile, let alone the efficacy of the traditional spring show. The bottom line is this. How out of touch can Primedia be with the needs of the high-end audio industry as to expect manufacturers to drop everything two months after CEDIA, one month after AES, and six weeks before Christmas, right in the middle of their busiest selling season, as they desperately try to FILL ORDERS FOR THEIR PAYING CUSTOMERS and prepare for the January 2004 Consumer Electronics Show so that they can blow off a week of time they can’t spare and tens of thousands of dollars they don’t have to make happy talk with a bunch of tire kickers in San Francisco? [c]HIPSTER[n] Read Chip's HE 2003 Show Report at 6moons.com

|

This tendency to argue for one style of reproduction while marginalizing another

reinforces the kind of silly fragmentation that puts so much distance between this thing

of ours and the very people we are trying to reach (save for the biannual "Look at

this supercilious rich clown with the $25,000 speaker cables" article in the New

York Times). It runs much deeper than simply debating the relative merits of analog

over digital or vacuum tubes versus solid state. No, we’ve further alienated the

unwashed and each other with interminable chin music about the merits of triode over

pentode, tetrode, and Ultralinear, pausing only to reload and chastise heretics regarding

the virtues of single-ended triode over push/pull, low power over high power, bass reflex

enclosures over transmission lines, horns over dynamic, planars over electrostatics, first

order over third order. How many angels can sit on the head of a pin? Never mind the

lunatic fringe who paint Stereophile editor John Atkinson as a spawn of Satan and

routinely bait him into coming on line to engage in mortal combat, and who impugn the

honor of any audio critic who praises a piece of gear they feel is unworthy by their

impeccable lights, and who therefore must be paid underlings of Baal. (If only we had

their gigs, we’d show ‘em how it’s supposed to be done.) Such

imperious fundamentalist pronouncements, narrow elitism, and transparent snobbery—the

bluster of feigned authority—runs rampant in this thing of ours.

This tendency to argue for one style of reproduction while marginalizing another

reinforces the kind of silly fragmentation that puts so much distance between this thing

of ours and the very people we are trying to reach (save for the biannual "Look at

this supercilious rich clown with the $25,000 speaker cables" article in the New

York Times). It runs much deeper than simply debating the relative merits of analog

over digital or vacuum tubes versus solid state. No, we’ve further alienated the

unwashed and each other with interminable chin music about the merits of triode over

pentode, tetrode, and Ultralinear, pausing only to reload and chastise heretics regarding

the virtues of single-ended triode over push/pull, low power over high power, bass reflex

enclosures over transmission lines, horns over dynamic, planars over electrostatics, first

order over third order. How many angels can sit on the head of a pin? Never mind the

lunatic fringe who paint Stereophile editor John Atkinson as a spawn of Satan and

routinely bait him into coming on line to engage in mortal combat, and who impugn the

honor of any audio critic who praises a piece of gear they feel is unworthy by their

impeccable lights, and who therefore must be paid underlings of Baal. (If only we had

their gigs, we’d show ‘em how it’s supposed to be done.) Such

imperious fundamentalist pronouncements, narrow elitism, and transparent snobbery—the

bluster of feigned authority—runs rampant in this thing of ours.  Is it any wonder that we find ourselves preaching almost exclusively to the

congregation? So much so that our industry has come to depend on a dedicated core of gear

heads and frivolous hobbyists to re-up again and again and again, all the while failing to

attract new buyers or training sales personnel to educate new consumers and hook the

really big fish. In depending upon such an in-bred audience—many of whom seem to

regard high end audio not as a door to perception but as a track meet in which one

competitor seeks to sample more bottles of wine than the next—two-channel

manufacturers and retailers find themselves in a bind. The emergence of Audiogon

is emblematic of where all of this marginalization has brought us. Hobbyists no longer

participate in a living, breathing marketplace, but whore out trendy,

here-today-gone-tomorrow products that have no lasting value, undermining the market for

new, lasting-quality gear by reallocating money that usually went to retailers in the form

of profit margins and trade-ins to haggle dubiously amongst each other (then adding insult

to injury by wasting manufacturers’ time with endless queries as to the latest

internet bargain—validate my decisions, reassure me that I’ll be happy). Never

mind customer service or warranties, having a store and a company stand behind said

services and products, or dealing with qualified people who understand that a great audio

system, like fine cuisine, is not simply a matter of having the fanciest ingredients, but

of knowing how to harmonize all of those elements into something greater than the sum

of its parts.

Is it any wonder that we find ourselves preaching almost exclusively to the

congregation? So much so that our industry has come to depend on a dedicated core of gear

heads and frivolous hobbyists to re-up again and again and again, all the while failing to

attract new buyers or training sales personnel to educate new consumers and hook the

really big fish. In depending upon such an in-bred audience—many of whom seem to

regard high end audio not as a door to perception but as a track meet in which one

competitor seeks to sample more bottles of wine than the next—two-channel

manufacturers and retailers find themselves in a bind. The emergence of Audiogon

is emblematic of where all of this marginalization has brought us. Hobbyists no longer

participate in a living, breathing marketplace, but whore out trendy,

here-today-gone-tomorrow products that have no lasting value, undermining the market for

new, lasting-quality gear by reallocating money that usually went to retailers in the form

of profit margins and trade-ins to haggle dubiously amongst each other (then adding insult

to injury by wasting manufacturers’ time with endless queries as to the latest

internet bargain—validate my decisions, reassure me that I’ll be happy). Never

mind customer service or warranties, having a store and a company stand behind said

services and products, or dealing with qualified people who understand that a great audio

system, like fine cuisine, is not simply a matter of having the fanciest ingredients, but

of knowing how to harmonize all of those elements into something greater than the sum

of its parts.  I wanted to see how things shook out as we lurched toward the Christmas selling

season and the January 2004 CES in Las Vegas because I was very disturbed by the deep

undercurrents of frustration simmering beneath the surface of all those happy faces

presented to the public at the St. Francis Westin. A lot of major

companies—significant players in our industry, and some of Stereophile’s

most significant advertisers—very consciously chose not to exhibit at the San

Francisco show. Oh, many of them were there, making the rounds, touching bases with the

public—they just decided not to plunk down big ducats for a room. Which illustrates

just how tenuous the relationship between consumers, manufacturers, and the media

currently is in this economy, and how deep the feelings of frustration were amongst many

exhibitors and non-exhibitors with whom I spoke.

I wanted to see how things shook out as we lurched toward the Christmas selling

season and the January 2004 CES in Las Vegas because I was very disturbed by the deep

undercurrents of frustration simmering beneath the surface of all those happy faces

presented to the public at the St. Francis Westin. A lot of major

companies—significant players in our industry, and some of Stereophile’s

most significant advertisers—very consciously chose not to exhibit at the San

Francisco show. Oh, many of them were there, making the rounds, touching bases with the

public—they just decided not to plunk down big ducats for a room. Which illustrates

just how tenuous the relationship between consumers, manufacturers, and the media

currently is in this economy, and how deep the feelings of frustration were amongst many

exhibitors and non-exhibitors with whom I spoke.  Which begs my other question… for how long? Because while the children of

Israel continue to wander in the Egypt-land of this economic desert, the corporate

Pharaohs at Primedia, saddled with an enormous vig, have reduced the flow of fructifying

water to each and every one of their publishing properties, none more so than Stereophile.

Or to paraphrase that corporate visionary, Tony Soprano, "In this thing of ours, shit

runs downhill, money runs back up."

Which begs my other question… for how long? Because while the children of

Israel continue to wander in the Egypt-land of this economic desert, the corporate

Pharaohs at Primedia, saddled with an enormous vig, have reduced the flow of fructifying

water to each and every one of their publishing properties, none more so than Stereophile.

Or to paraphrase that corporate visionary, Tony Soprano, "In this thing of ours, shit

runs downhill, money runs back up."  Hello?! Instead of readers and audio industry-types being able to

peruse the thoughtful, informed audio insights of Sam Tellig, Michael Fremer, John

Atkinson, Kal Rubinson, Larry Greenhill, Robert Deutsch, Brian Damkroger, John Marks, Paul

Bolin, and Wes Phillips, they were treated instead to an eight-page photo essay. As one

manufacturer put it, "Would you mind telling me what the hell that was about?"

This is just the kind of half-hearted advertorial tidbit that mass-market publications

toss the audio industry’s way once a year as porcine ad reps forage for advertising

truffles. Decidedly underwhelming by comparison with the real-time coverage of

knowledgeable audiophiles like Srajan Ebaen on the 6Moons website or Wes Phillips

on Stereophile’s own website. Talk about sending mixed messages to your best

customers!

Hello?! Instead of readers and audio industry-types being able to

peruse the thoughtful, informed audio insights of Sam Tellig, Michael Fremer, John

Atkinson, Kal Rubinson, Larry Greenhill, Robert Deutsch, Brian Damkroger, John Marks, Paul

Bolin, and Wes Phillips, they were treated instead to an eight-page photo essay. As one

manufacturer put it, "Would you mind telling me what the hell that was about?"

This is just the kind of half-hearted advertorial tidbit that mass-market publications

toss the audio industry’s way once a year as porcine ad reps forage for advertising

truffles. Decidedly underwhelming by comparison with the real-time coverage of

knowledgeable audiophiles like Srajan Ebaen on the 6Moons website or Wes Phillips

on Stereophile’s own website. Talk about sending mixed messages to your best

customers!

Still, while my sympathies clearly lie with the high end audio manufacturers and

retailers, the magazine and its writers, it doesn’t seem quite appropriate to simply

heap all the blame on Primedia and give John Atkinson a total pass. I have great affection

and admiration for John. He is a talented writer, musician, and recording enthusiast, and

a devout audiophile with a real passion for music. He and Larry Greenhill evolved J.

Gordon Holt’s original vision of Stereophile, disciplined it, and put it on

a solid business footing. I’m reminded of an aphorism from the Kant of J. Gordon.

I’m paraphrasing loosely, but the gist of it is that if the midrange is right, you

can work around the bass and the treble, but if the midrange is wrong, nothing else

matters. Stereophile (and The Absolute Sound) recast the discussion of

audio gear… for the better. The manner in which an audio system communicated the

emotional experience of a musical performance and reproduced the parameters of a live

acoustic experience became paramount, superseding the viewpoint of cold objectivists like

Julian Hirsch, for whom measurements were all that mattered. (If they measured the same,

then they sounded the same, or so the old saw went.) The growth of the magazine and of

high end audio paralleled each other well into the 90s, during which time Atkinson

nurtured the work of numerous audio writers, myself included.

Still, while my sympathies clearly lie with the high end audio manufacturers and

retailers, the magazine and its writers, it doesn’t seem quite appropriate to simply

heap all the blame on Primedia and give John Atkinson a total pass. I have great affection

and admiration for John. He is a talented writer, musician, and recording enthusiast, and

a devout audiophile with a real passion for music. He and Larry Greenhill evolved J.

Gordon Holt’s original vision of Stereophile, disciplined it, and put it on

a solid business footing. I’m reminded of an aphorism from the Kant of J. Gordon.

I’m paraphrasing loosely, but the gist of it is that if the midrange is right, you

can work around the bass and the treble, but if the midrange is wrong, nothing else

matters. Stereophile (and The Absolute Sound) recast the discussion of

audio gear… for the better. The manner in which an audio system communicated the

emotional experience of a musical performance and reproduced the parameters of a live

acoustic experience became paramount, superseding the viewpoint of cold objectivists like

Julian Hirsch, for whom measurements were all that mattered. (If they measured the same,

then they sounded the same, or so the old saw went.) The growth of the magazine and of

high end audio paralleled each other well into the 90s, during which time Atkinson

nurtured the work of numerous audio writers, myself included.  Now that summer has passed, and the inevitable economic drive towards Christmas

has begun, the folks at Primedia need to reassess, refocus, and rededicate themselves to

the magazine in general—AND TO THE HIGH END AUDIO INDUSTRY IN PARTICULAR—by

recognizing their responsibility to prime the pump as it were, and support the high end

audio industry.

Now that summer has passed, and the inevitable economic drive towards Christmas

has begun, the folks at Primedia need to reassess, refocus, and rededicate themselves to

the magazine in general—AND TO THE HIGH END AUDIO INDUSTRY IN PARTICULAR—by

recognizing their responsibility to prime the pump as it were, and support the high end

audio industry.  It is the professional responsibility of this show’s sponsors to negotiate

with the unions on their exhibitors’ behalf. I mean, in New York City, when you hire

an architect to develop a property, you are not simply paying for their design expertise,

but for their knowledge of suppliers, building codes, local ordinances, and union

compliance. It is simply unconscionable to abdicate this responsibility and toss your

paying customers to the wolves. An absolutely iron-clad ceiling on drayage costs is

necessary to bring back those exhibitors who’ve bailed out of recent shows, let alone

getting them to sign on for two! Likewise, here’s hoping that Primedia facilitates

things so as to make it that much easier for companies to represent themselves, make

contact with the public, generate sales, and sustain growth to the point where they can

afford to expand their advertising budgets in search of new customers. Is this really such

a radical idea? That when business is flat, you do something to give it a boost? That in

times of economic downturn, you reinvest, recapitalize in order to fully take advantage of

an economic upturn?

It is the professional responsibility of this show’s sponsors to negotiate

with the unions on their exhibitors’ behalf. I mean, in New York City, when you hire

an architect to develop a property, you are not simply paying for their design expertise,

but for their knowledge of suppliers, building codes, local ordinances, and union

compliance. It is simply unconscionable to abdicate this responsibility and toss your

paying customers to the wolves. An absolutely iron-clad ceiling on drayage costs is

necessary to bring back those exhibitors who’ve bailed out of recent shows, let alone

getting them to sign on for two! Likewise, here’s hoping that Primedia facilitates

things so as to make it that much easier for companies to represent themselves, make

contact with the public, generate sales, and sustain growth to the point where they can

afford to expand their advertising budgets in search of new customers. Is this really such

a radical idea? That when business is flat, you do something to give it a boost? That in

times of economic downturn, you reinvest, recapitalize in order to fully take advantage of

an economic upturn?  Hmmm. Wondering how those numbers were calculated? I sure am. Let’s just

dwell on that consumer traffic figure for a nonce: 15,123. I think it’s fair to say

that there were not 15,123 paying customers at the St. Francis Westin. Realistically

speaking, most people in the industry I speak with presume that the term "consumer

traffic" refers to the number of times the bar code on an attendee’s badge was

digitally scanned by show personnel. Since a three-day pass costs $35 and a single

day’s pass goes for $25, let’s figure roughly 6000 attendees at $35 a pop based

on three days of attendance. That translates into $210,000 of pure profit, never you mind

how much Primedia clears from exhibitors for the rooms and suites after covering sundry

expenses, such as that of concert artists and show personnel, plus transportation and

lodging for the various magazines’ editorial staff and sales personnel.

Hmmm. Wondering how those numbers were calculated? I sure am. Let’s just

dwell on that consumer traffic figure for a nonce: 15,123. I think it’s fair to say

that there were not 15,123 paying customers at the St. Francis Westin. Realistically

speaking, most people in the industry I speak with presume that the term "consumer

traffic" refers to the number of times the bar code on an attendee’s badge was

digitally scanned by show personnel. Since a three-day pass costs $35 and a single

day’s pass goes for $25, let’s figure roughly 6000 attendees at $35 a pop based

on three days of attendance. That translates into $210,000 of pure profit, never you mind

how much Primedia clears from exhibitors for the rooms and suites after covering sundry

expenses, such as that of concert artists and show personnel, plus transportation and

lodging for the various magazines’ editorial staff and sales personnel.  It’s one thing to make bricks without straw, but it’s quite another to

try and make mortar without water. Even perennial powerhouses such as Sony have absorbed

their fair share of economic body blows this past year, and if Sony is hurting, what does

this portend for the industry at large? It means that while business has started to turn

around in the fourth quarter of 2003, budgets are still tight, while consumers and

producers alike are still tentative and wary, looking to get the most bang for their buck.

It’s one thing to make bricks without straw, but it’s quite another to

try and make mortar without water. Even perennial powerhouses such as Sony have absorbed

their fair share of economic body blows this past year, and if Sony is hurting, what does

this portend for the industry at large? It means that while business has started to turn

around in the fourth quarter of 2003, budgets are still tight, while consumers and

producers alike are still tentative and wary, looking to get the most bang for their buck.